Introduction

As the name suggests, random forest models basically contain an ensemble of decision tree models, with each decision tree predicting the same response variable. The response may be categorical, in which case being a classification problem, or continuous / numerical, being a regression problem.

In this short tutorial, we will go through the use of tree-based methods (decision tree, bagging model, and random forest) for both classification and regression problems.

This tutorial is divided into two sections. We will first use tree-based methods for classification on the spam dataset from the kernlab package. Subsequently, we will apply these methods on a regression problem, with the imports85 dataset from the randomForest package.

Tree-based methods for classification

Preparation

Let’s start by loading the spam dataset and doing some preparations:

# packages that we will need:

# @ kernlab: for the spam dataset

# @ tree: for decision tree construction

# @ randomForest: for bagging and RF

# @ beepr: for a little beep

# @ pROC: for plotting of ROC

# code snippet to install and load multiple packages at once

# pkgs <- c("kernlab","tree","randomForest","beepr","pROC")

# sapply(pkgs,FUN=function(p){

# print(p)

# if(!require(p)) install.packages(p)

# require(p)

# })

# load required packages

suppressWarnings(library(kernlab))

suppressWarnings(library(tree))

suppressWarnings(library(randomForest))

## randomForest 4.6-14

## Type rfNews() to see new features/changes/bug fixes.

suppressWarnings(library(beepr)) # try it! beep()

suppressWarnings(library(pROC))

## Type 'citation("pROC")' for a citation.

##

## Attaching package: 'pROC'

## The following objects are masked from 'package:stats':

##

## cov, smooth, var

# load dataset

data(spam)

# take a look

str(spam)

## 'data.frame': 4601 obs. of 58 variables:

## $ make : num 0 0.21 0.06 0 0 0 0 0 0.15 0.06 ...

## $ address : num 0.64 0.28 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0.12 ...

## $ all : num 0.64 0.5 0.71 0 0 0 0 0 0.46 0.77 ...

## $ num3d : num 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ...

## $ our : num 0.32 0.14 1.23 0.63 0.63 1.85 1.92 1.88 0.61 0.19 ...

## $ over : num 0 0.28 0.19 0 0 0 0 0 0 0.32 ...

## $ remove : num 0 0.21 0.19 0.31 0.31 0 0 0 0.3 0.38 ...

## $ internet : num 0 0.07 0.12 0.63 0.63 1.85 0 1.88 0 0 ...

## $ order : num 0 0 0.64 0.31 0.31 0 0 0 0.92 0.06 ...

## $ mail : num 0 0.94 0.25 0.63 0.63 0 0.64 0 0.76 0 ...

## $ receive : num 0 0.21 0.38 0.31 0.31 0 0.96 0 0.76 0 ...

## $ will : num 0.64 0.79 0.45 0.31 0.31 0 1.28 0 0.92 0.64 ...

## $ people : num 0 0.65 0.12 0.31 0.31 0 0 0 0 0.25 ...

## $ report : num 0 0.21 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ...

## $ addresses : num 0 0.14 1.75 0 0 0 0 0 0 0.12 ...

## $ free : num 0.32 0.14 0.06 0.31 0.31 0 0.96 0 0 0 ...

## $ business : num 0 0.07 0.06 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ...

## $ email : num 1.29 0.28 1.03 0 0 0 0.32 0 0.15 0.12 ...

## $ you : num 1.93 3.47 1.36 3.18 3.18 0 3.85 0 1.23 1.67 ...

## $ credit : num 0 0 0.32 0 0 0 0 0 3.53 0.06 ...

## $ your : num 0.96 1.59 0.51 0.31 0.31 0 0.64 0 2 0.71 ...

## $ font : num 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ...

## $ num000 : num 0 0.43 1.16 0 0 0 0 0 0 0.19 ...

## $ money : num 0 0.43 0.06 0 0 0 0 0 0.15 0 ...

## $ hp : num 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ...

## $ hpl : num 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ...

## $ george : num 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ...

## $ num650 : num 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ...

## $ lab : num 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ...

## $ labs : num 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ...

## $ telnet : num 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ...

## $ num857 : num 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ...

## $ data : num 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0.15 0 ...

## $ num415 : num 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ...

## $ num85 : num 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ...

## $ technology : num 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ...

## $ num1999 : num 0 0.07 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ...

## $ parts : num 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ...

## $ pm : num 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ...

## $ direct : num 0 0 0.06 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ...

## $ cs : num 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ...

## $ meeting : num 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ...

## $ original : num 0 0 0.12 0 0 0 0 0 0.3 0 ...

## $ project : num 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0.06 ...

## $ re : num 0 0 0.06 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ...

## $ edu : num 0 0 0.06 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ...

## $ table : num 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ...

## $ conference : num 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ...

## $ charSemicolon : num 0 0 0.01 0 0 0 0 0 0 0.04 ...

## $ charRoundbracket : num 0 0.132 0.143 0.137 0.135 0.223 0.054 0.206 0.271 0.03 ...

## $ charSquarebracket: num 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ...

## $ charExclamation : num 0.778 0.372 0.276 0.137 0.135 0 0.164 0 0.181 0.244 ...

## $ charDollar : num 0 0.18 0.184 0 0 0 0.054 0 0.203 0.081 ...

## $ charHash : num 0 0.048 0.01 0 0 0 0 0 0.022 0 ...

## $ capitalAve : num 3.76 5.11 9.82 3.54 3.54 ...

## $ capitalLong : num 61 101 485 40 40 15 4 11 445 43 ...

## $ capitalTotal : num 278 1028 2259 191 191 ...

## $ type : Factor w/ 2 levels "nonspam","spam": 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 ...In this example, we will attempt to predict whether an email is spam or nonspam. To do so, we will construct models on one subset of the data (training data), and use the constructed model on another disparate subset of the data (the testing data). This is known as cross validation.

# preparation for cross validation:

# split the dataset into 2 halves,

# 2300 samples for training and 2301 for testing

num.samples <- nrow(spam) # 4,601

num.train <- round(num.samples/2) # 2,300

num.test <- num.samples - num.train # 2,301

num.var <- ncol(spam) # 58

# set up the indices

set.seed(150715)

idx <- sample(1:num.samples)

train.idx <- idx[seq(num.train)]

test.idx <- setdiff(idx,train.idx)

# subset the data

spam.train <- spam[train.idx,]

spam.test <- spam[test.idx,]Taking a quick glance at the type variable:

table(spam.train$type)

##

## nonspam spam

## 1380 920

table(spam.test$type)

##

## nonspam spam

## 1408 893Decision tree

Now that we are done with the preparation, let’s start by constructing a decision tree model, using the tree package:

tree.mod <- tree(type ~ ., data = spam.train)Here’s how our model looks like:

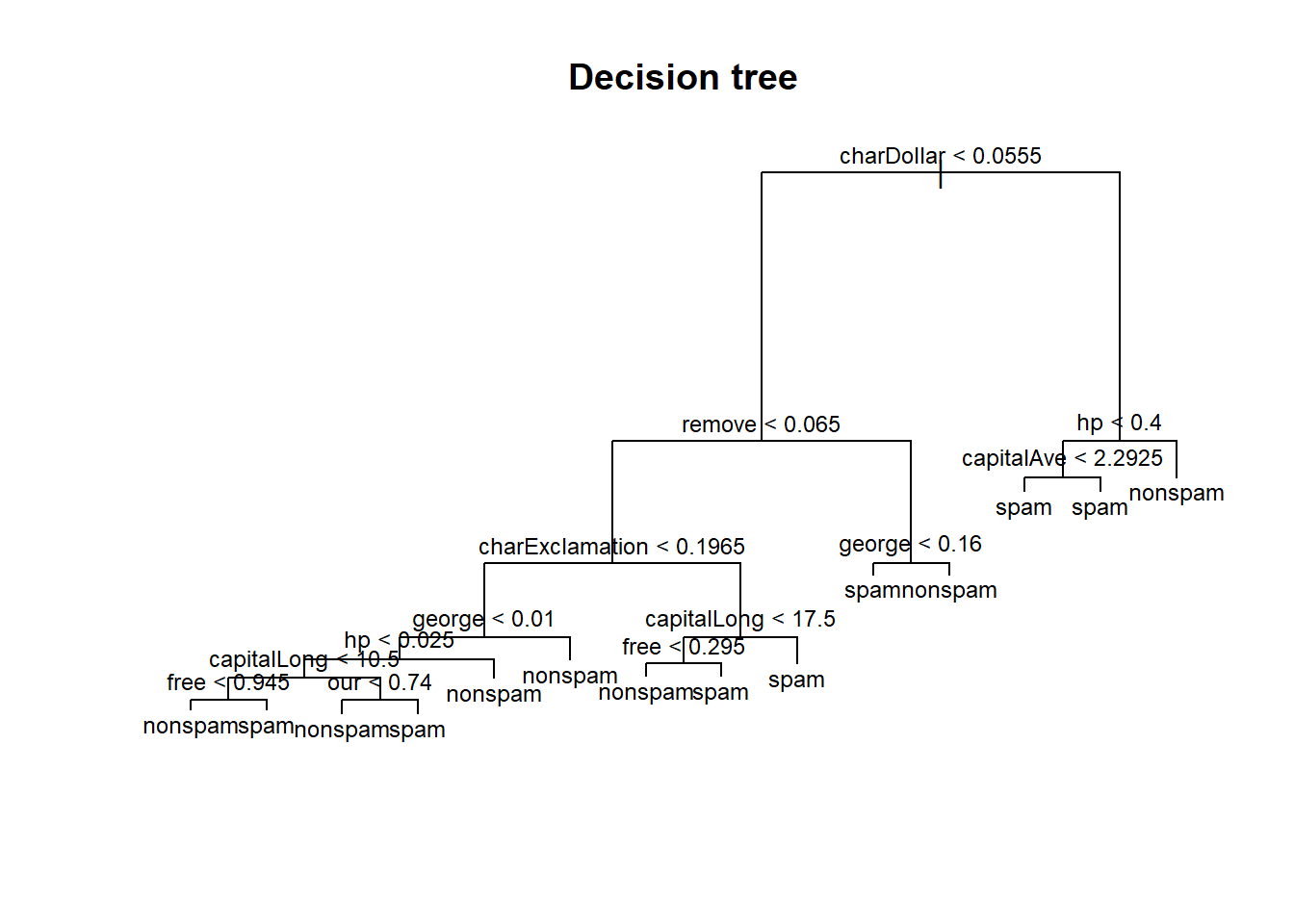

plot(tree.mod)

title("Decision tree")

text(tree.mod, cex = 0.75)

The model may be overtly complicated. Typically, after constructing a decision tree model, we may want to prune the model, by collapsing certain edges, nodes and leaves together without much loss of performance. This is done by iteratively comparing the number of leaf nodes with the model’s performance (by k-fold cross validation within the training set).

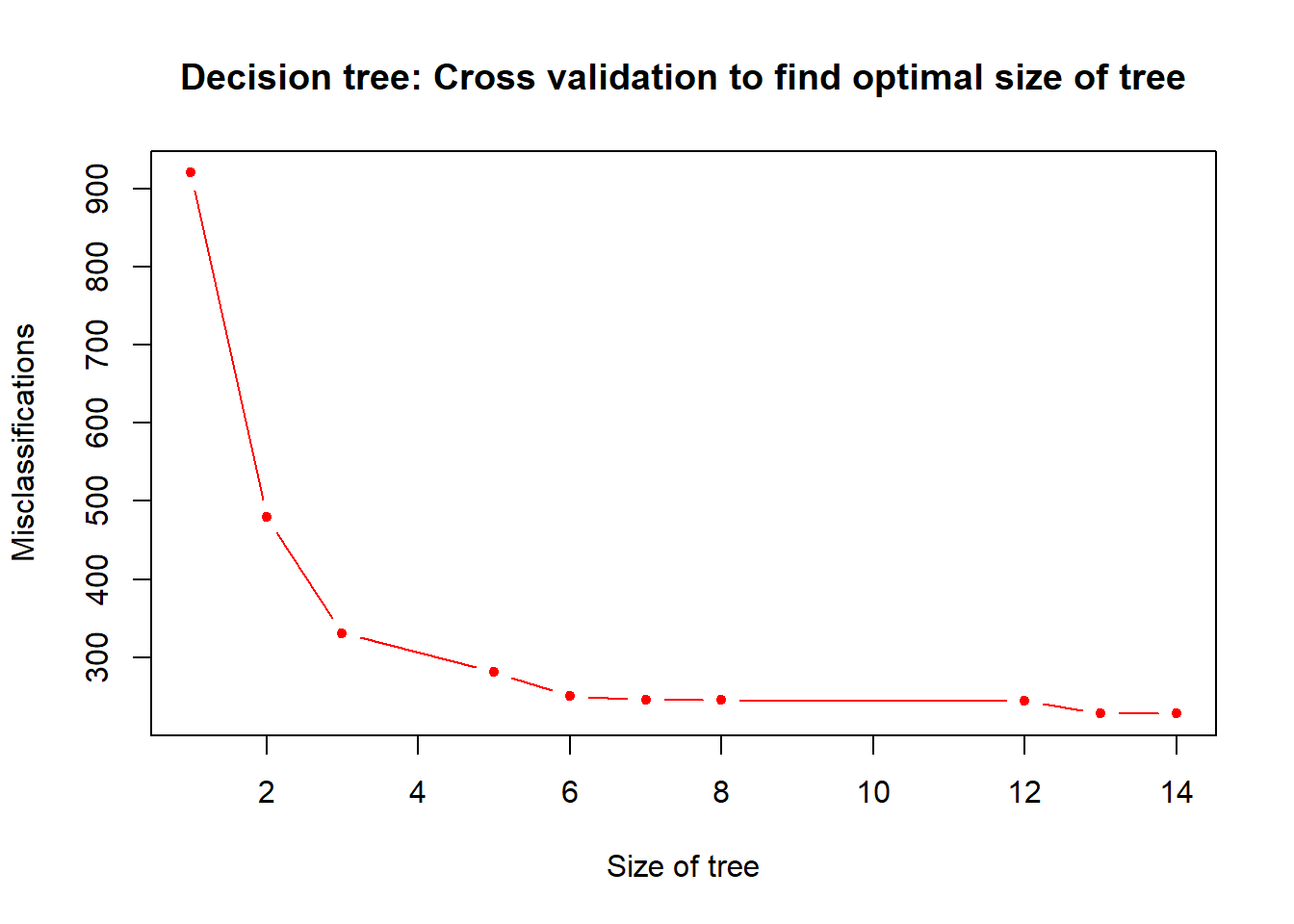

cv.prune <- cv.tree(tree.mod, FUN = prune.misclass)

plot(cv.prune$size, cv.prune$dev, pch = 20, col = "red", type = "b",

main = "Decision tree: Cross validation to find optimal size of tree",

xlab = "Size of tree", ylab = "Misclassifications")

Having 9 leaf nodes may be good (maximising performance while minimising complexity).

best.tree.size <- 9

# pruning (cost-complexity pruning)

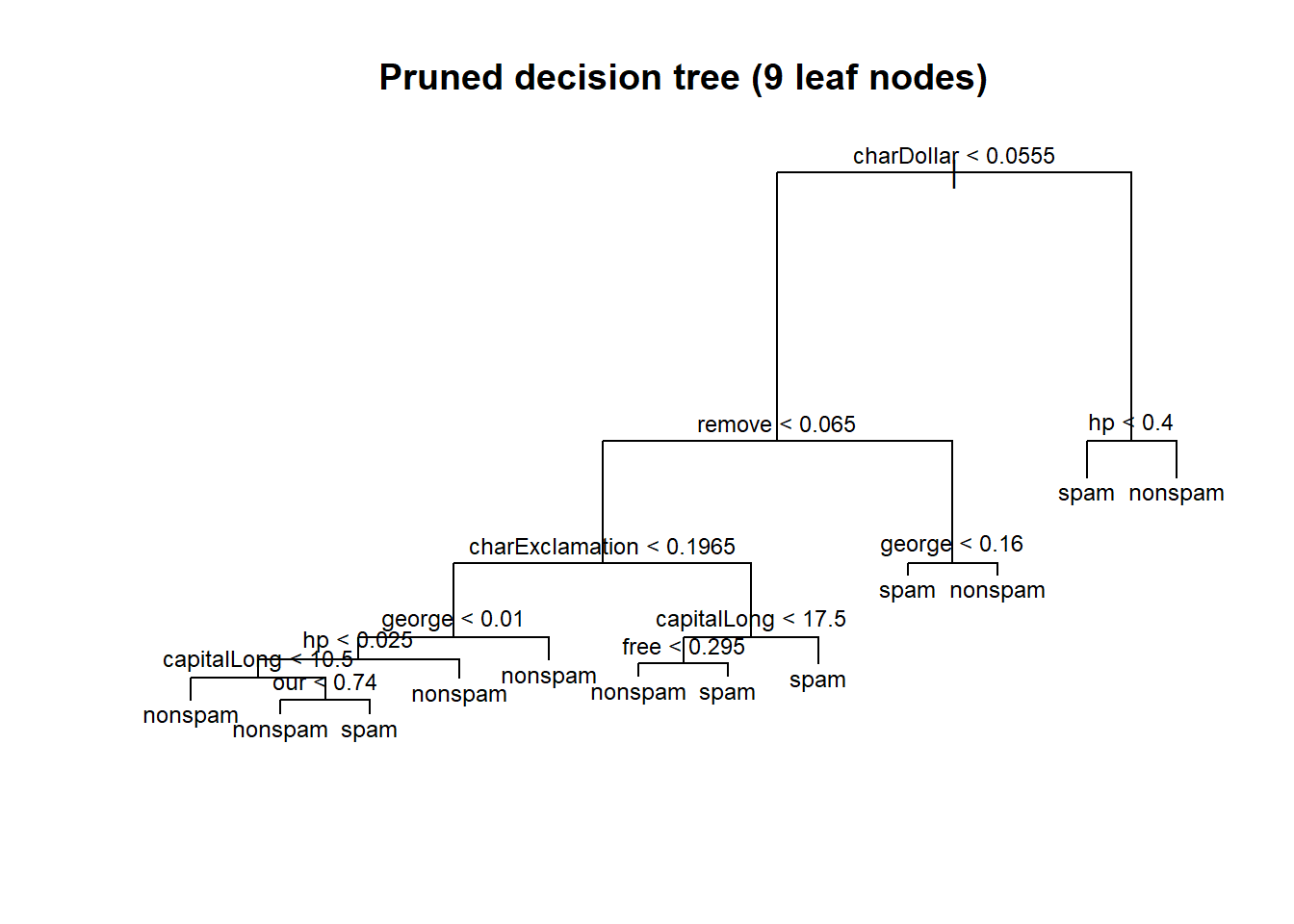

pruned.tree.mod <- prune.misclass(tree.mod, best = best.tree.size)

# here's the new tree model

plot(pruned.tree.mod)

title(paste("Pruned decision tree (", best.tree.size, " leaf nodes)",sep = ""))

text(pruned.tree.mod, cex = 0.75)

Now with our new model, let’s make some predictions on the testing data.

tree.pred <- predict(pruned.tree.mod,

subset(spam.test, select = -type),

type = "class")

# confusion matrix

# rows are the predicted classes

# columns are the actual classes

print(tree.pred.results <- table(tree.pred, spam.test$type))

##

## tree.pred nonspam spam

## nonspam 1325 120

## spam 83 773

# What is the accuracy of our tree model?

print(tree.accuracy <- (tree.pred.results[1,1] + tree.pred.results[2,2]) / sum(tree.pred.results))

## [1] 0.9117775Our decision tree model is able to predict spam vs. nonspam emails with about 91.18% accuracy. We will make comparisons of accuracies with other models later.

Bagging

Next, we turn our attention to the bagging model. Recall that bagging, a.k.a. bootstrap aggregating, is the process of sampling (with replacement), samples from the training data. Each of these subsets are known as bags, and we construct individual decision tree models using each of these bags. Finally, to make a classification prediction, we use the majority vote from the ensemble of decision tree models.

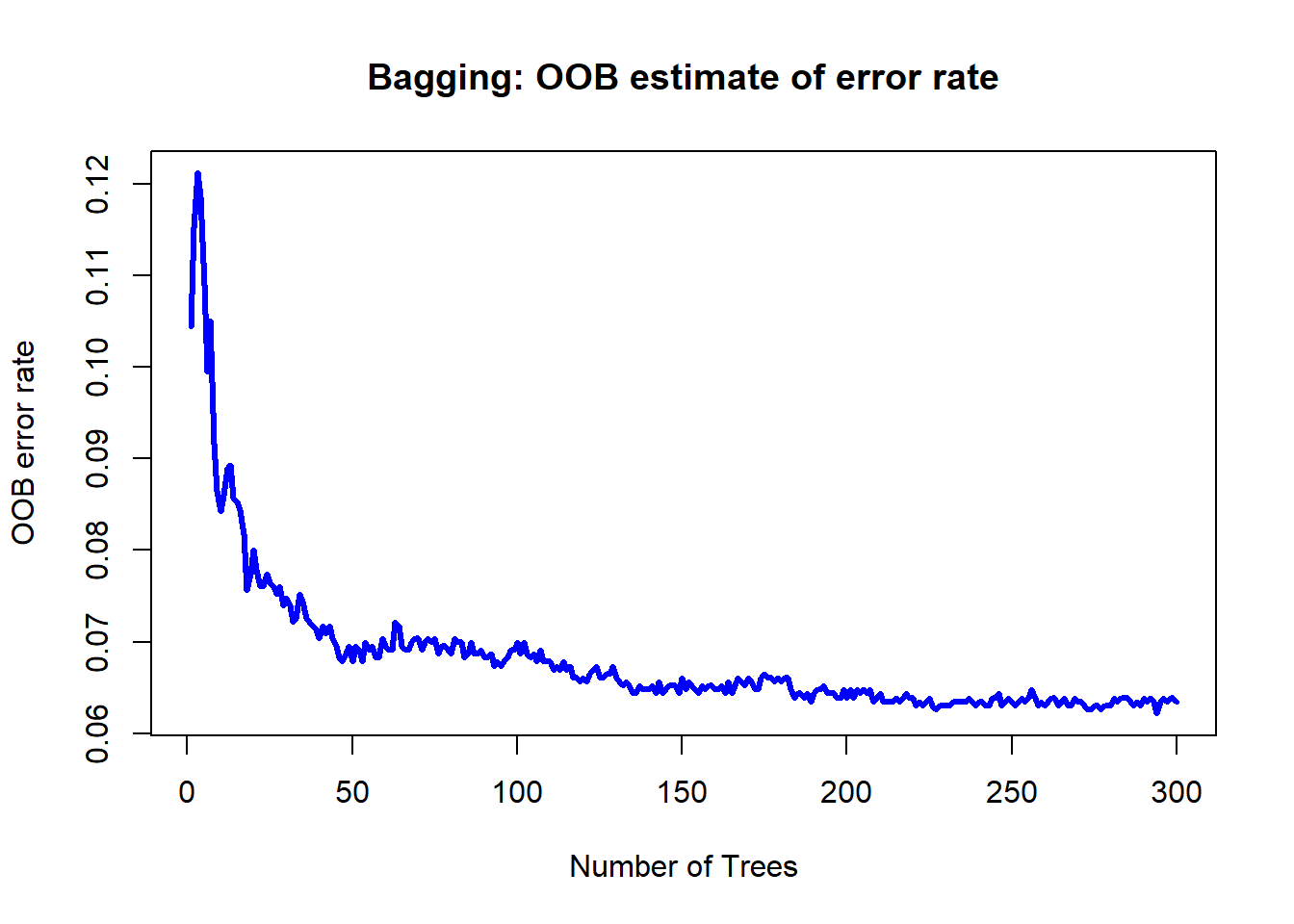

bg.mod<-randomForest(type ~ ., data = spam.train,

mtry = num.var - 1, # try all variables at each split, except the response variable

ntree = 300,

proximity = TRUE,

importance = TRUE)In the bagging, and also the random forest model, there are often only two hyperparameters that we are interested in: mtry, which is the number of variables to try from for each tree and at each split, and ntree, the number of trees in the ensemble. Tuning the number of trees is relatively easy by looking at the out-of-bag (OOB) error estimate of the ensemble at each step of the way. For more details, refer to the slides. We set proximity = TRUE and importance = TRUE, in order to get some form of visualization of the model, and the variable importances respectively.

plot(bg.mod$err.rate[,1], type = "l", lwd = 3, col = "blue",

main = "Bagging: OOB estimate of error rate",

xlab = "Number of Trees", ylab = "OOB error rate")

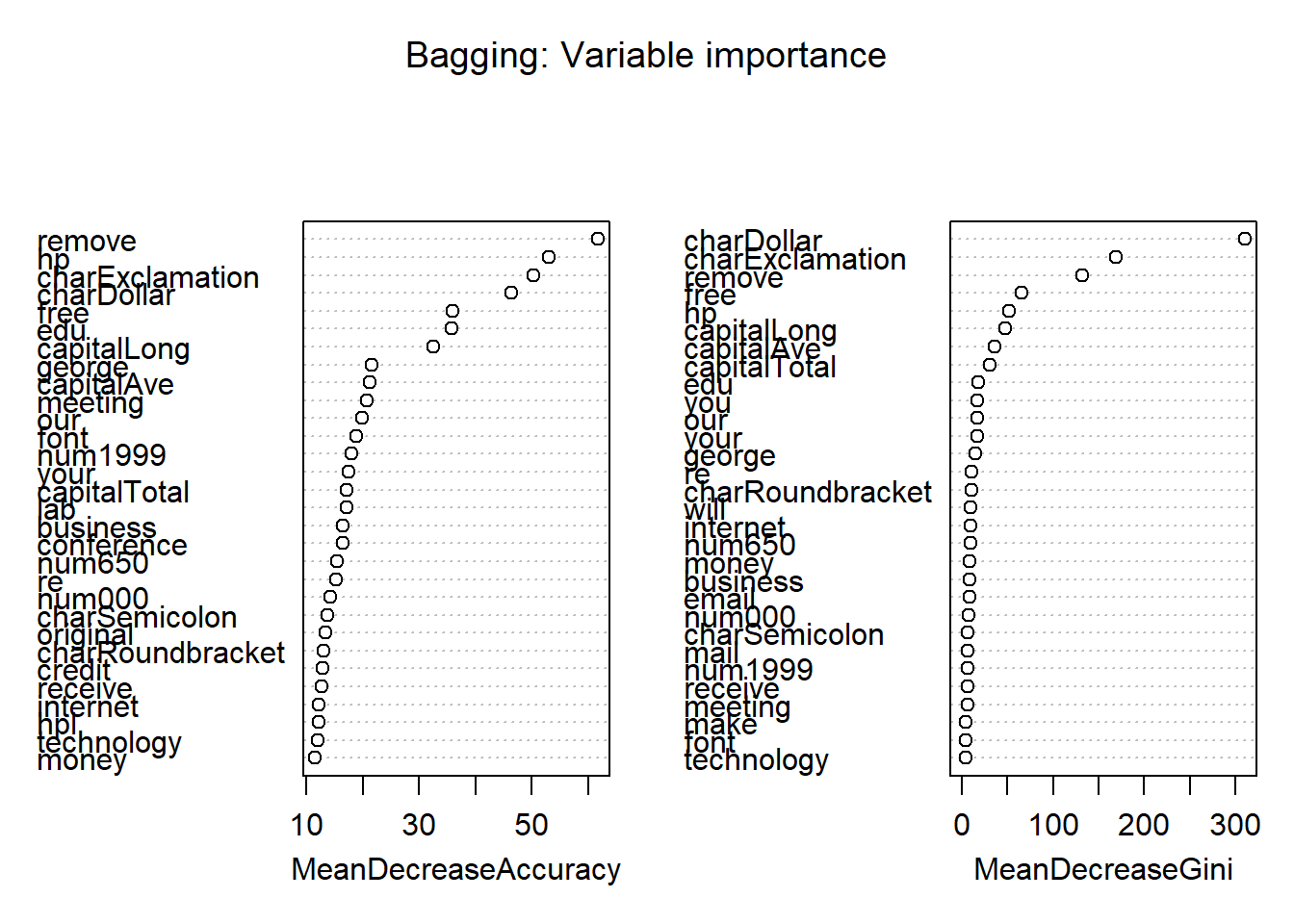

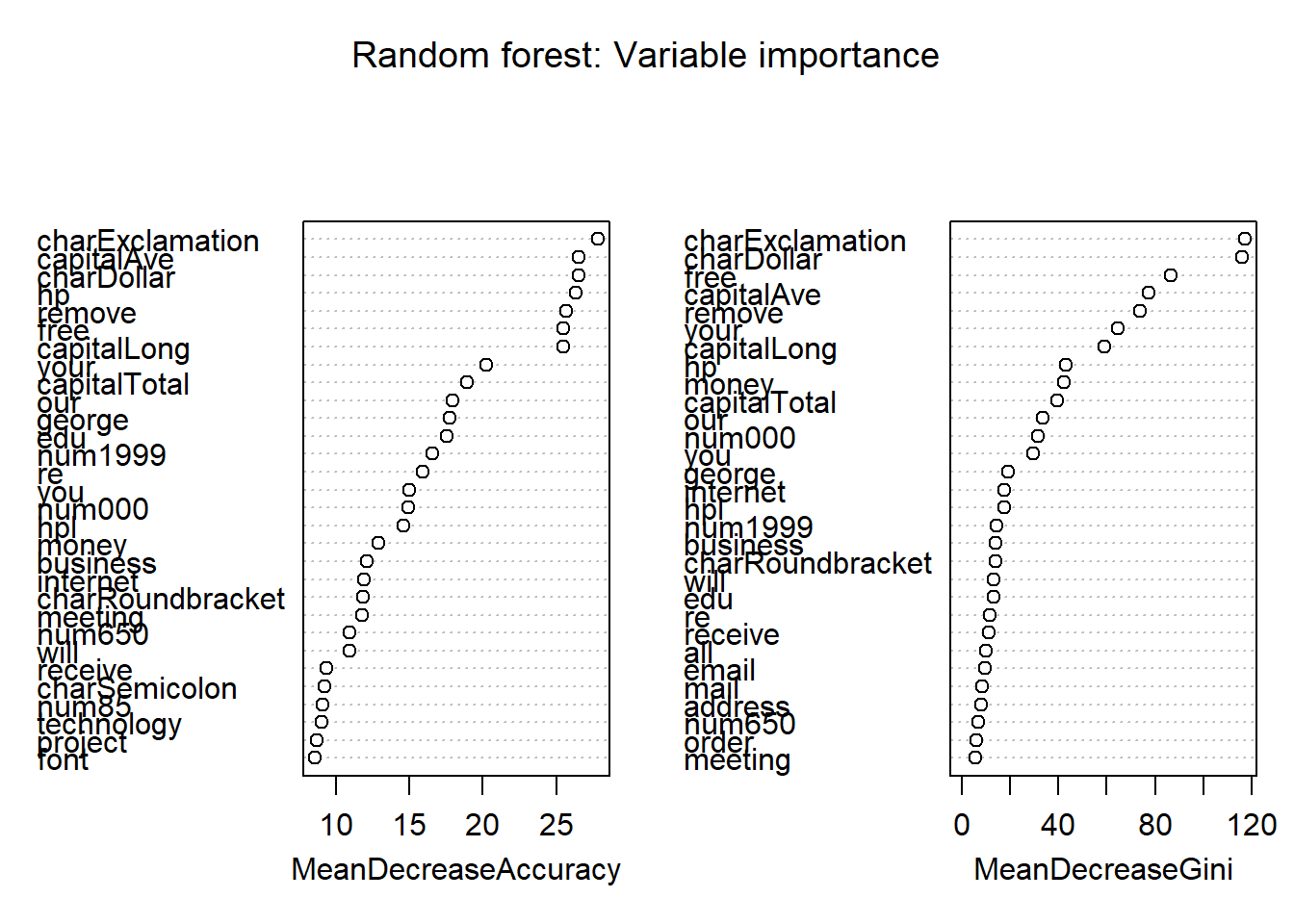

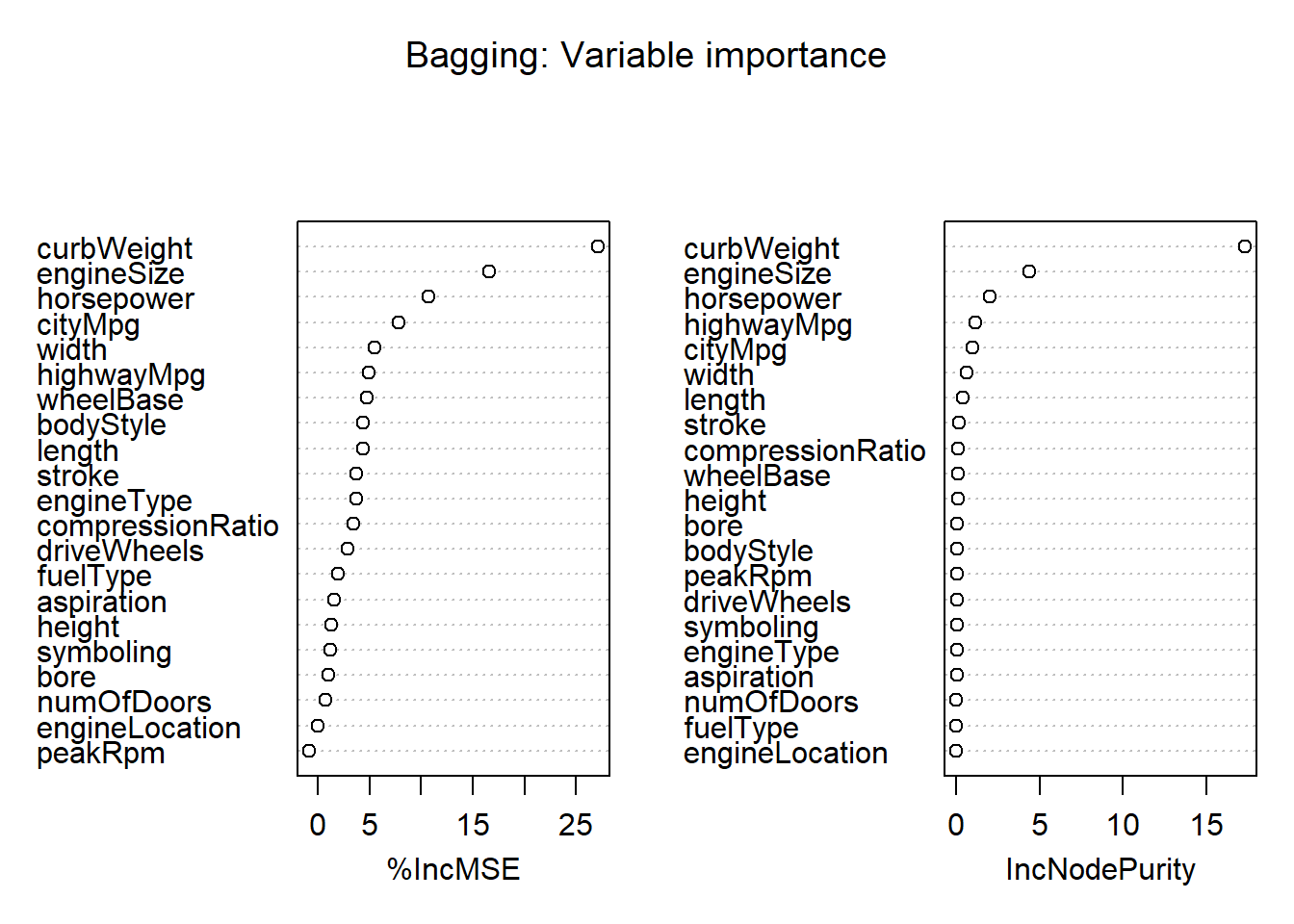

Here, 300 trees seems more than sufficient. One advantage of bagging and random forest models is that they provide a way of doing feature or variable selection, by considering the importance of each variable in the model. For exact details on how these importance measures are defined, refer to the slides.

varImpPlot(bg.mod,

main = "Bagging: Variable importance")

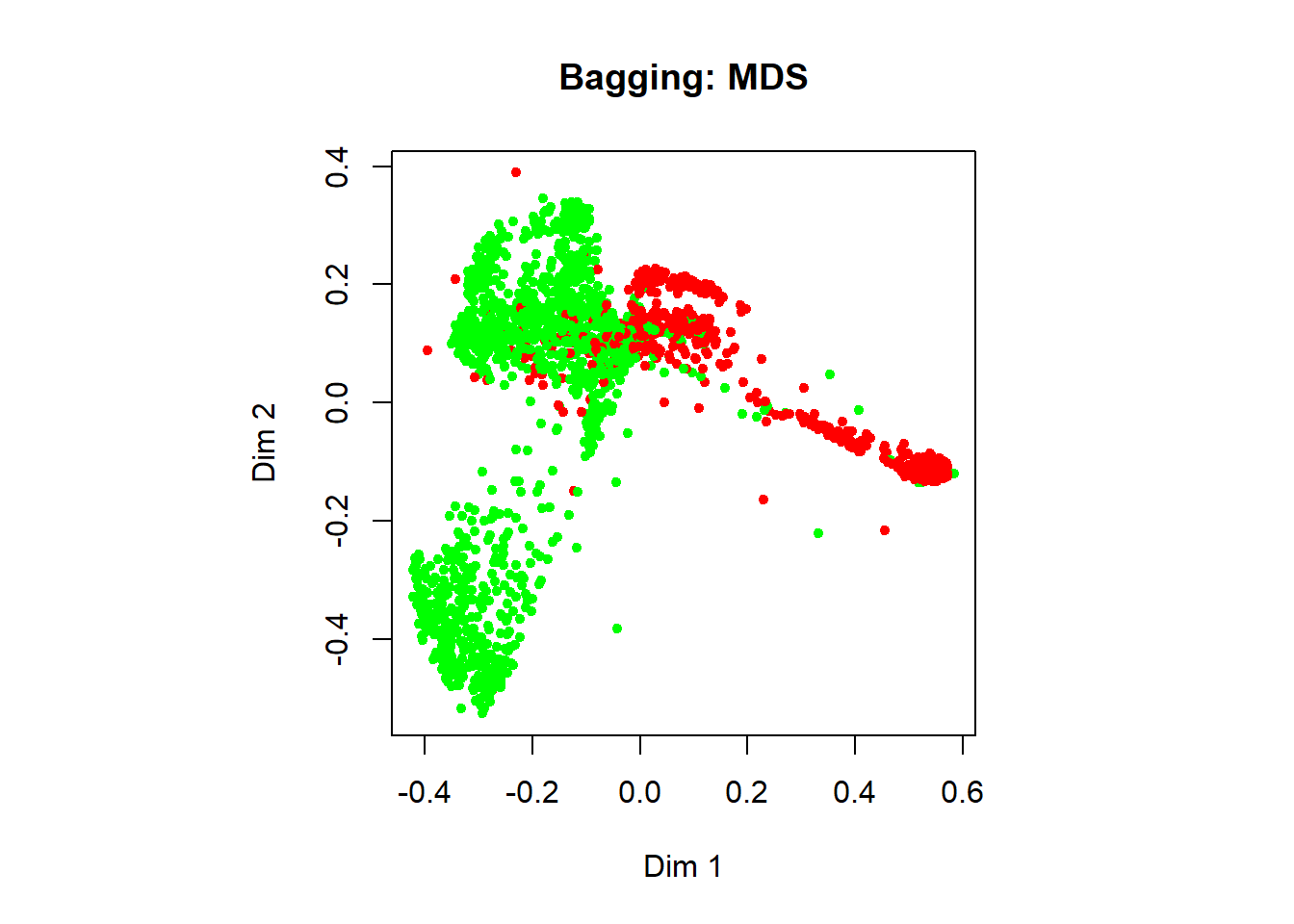

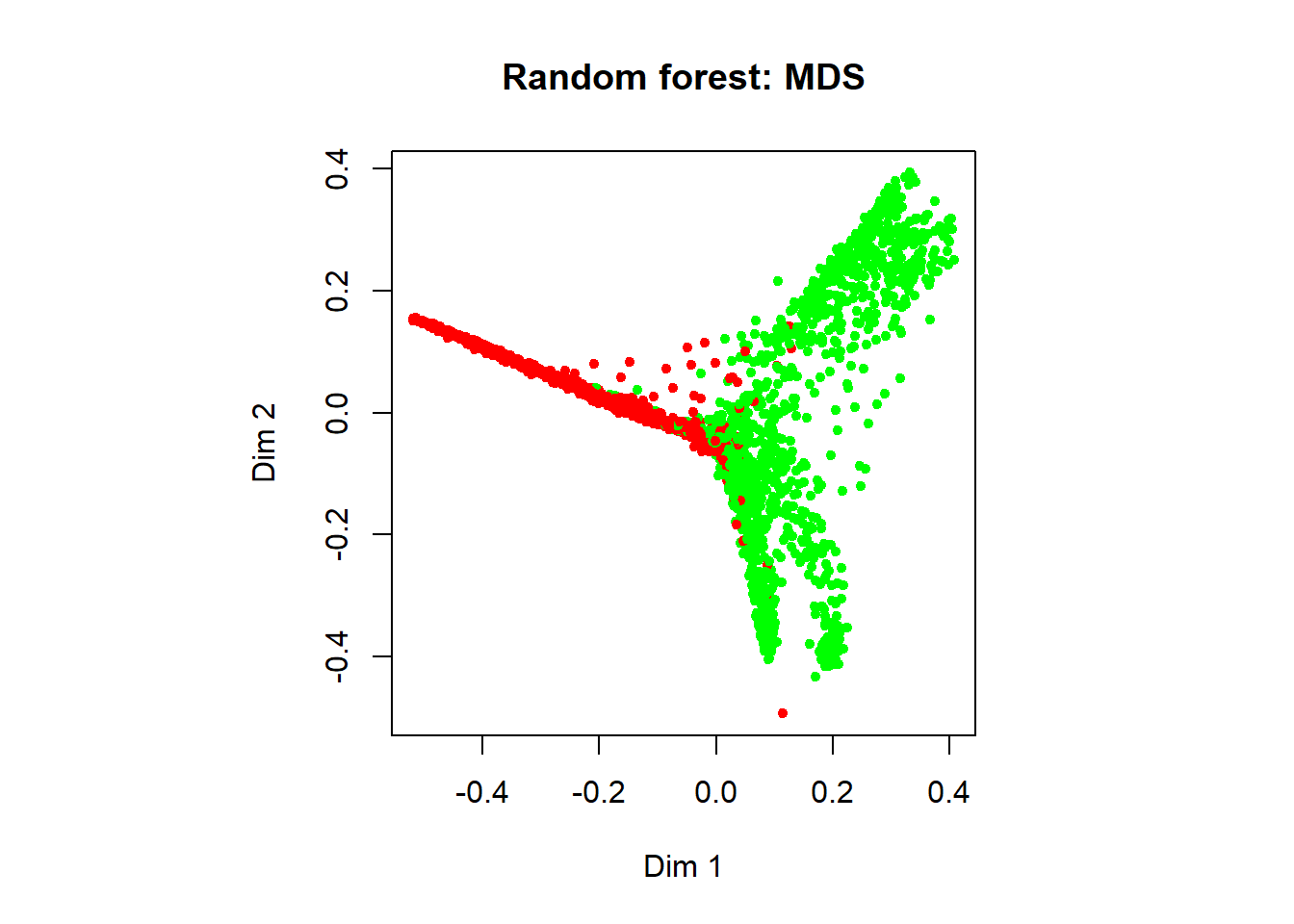

In addition, we can visualize the classification done by the model using a multidimensional plot on the proximity matrix. The green samples in the figure represent nonspams, while the red samples are spams.

MDSplot(bg.mod,

fac = spam.train$type,

palette = c("green","red"),

main = "Bagging: MDS")

Finally, let’s make some predictions on the testing data:

bg.pred <- predict(bg.mod,

subset(spam.test, select = -type),

type = "class")

# confusion matrix

# rows are the predicted classes

# columns are the actual classes

print(bg.pred.results <- table(bg.pred, spam.test$type))

##

## bg.pred nonspam spam

## nonspam 1358 78

## spam 50 815

# what is the accuracy of our bagging model?

print(bg.accuracy <- sum(diag((bg.pred.results))) / sum(bg.pred.results))

## [1] 0.944372Our bagging model predicts whether an email is spam or not with about 94.44% accuracy.

Random Forest

The only difference between the bagging model and random forest model is that the latter uses chooses only from a subset of variables to split on at each node of each tree. In other words, only the mtry argument differs between bagging and random forest.

rf.mod <- randomForest(type ~ ., data = spam.train,

mtry = floor(sqrt(num.var - 1)), # 7; only difference from bagging is here

ntree = 300,

proximity = TRUE,

importance = TRUE)

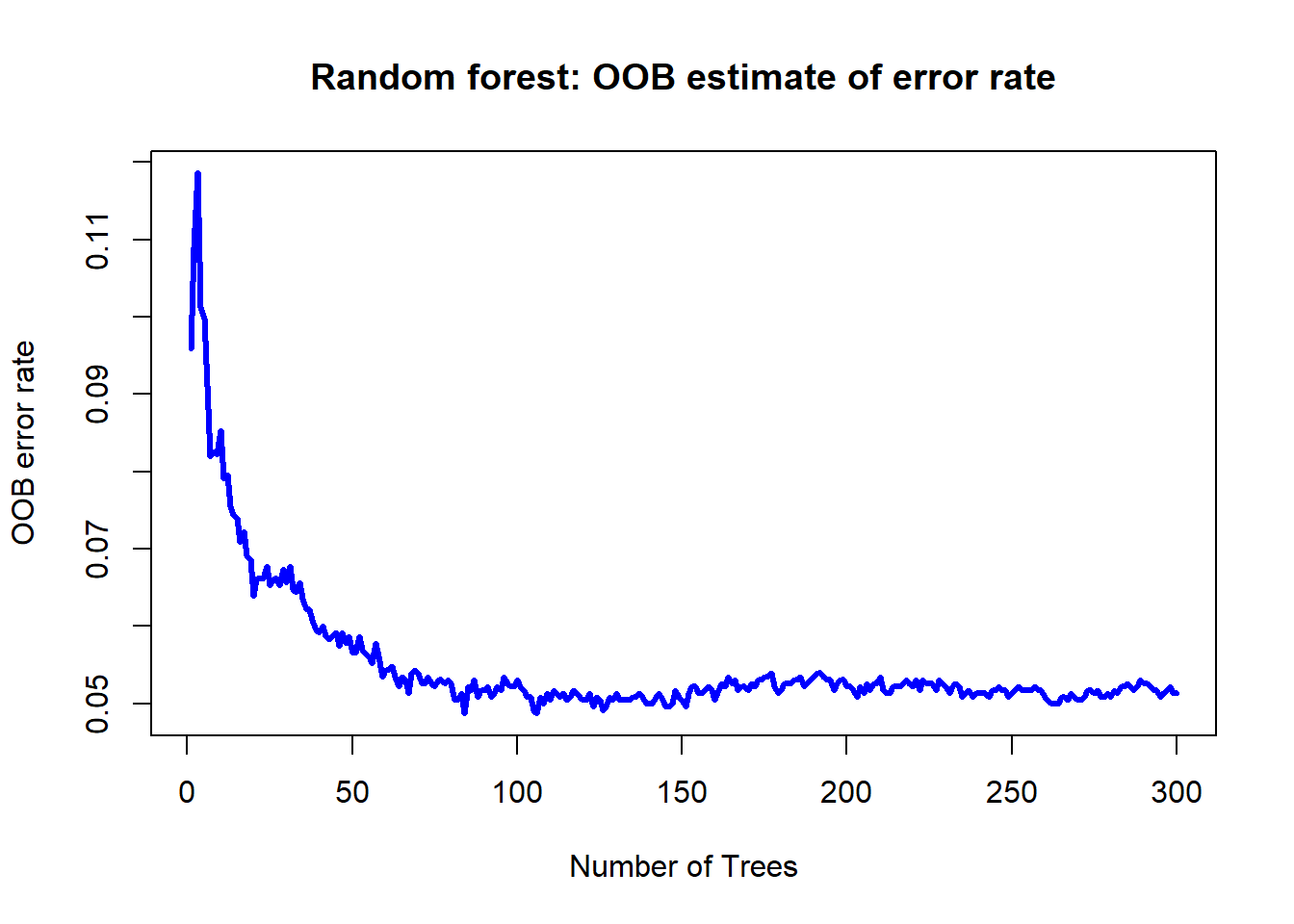

# Out-of-bag (OOB) error rate as a function of num. of trees:

plot(rf.mod$err.rate[,1], type = "l", lwd = 3, col = "blue",

main = "Random forest: OOB estimate of error rate",

xlab = "Number of Trees", ylab = "OOB error rate")

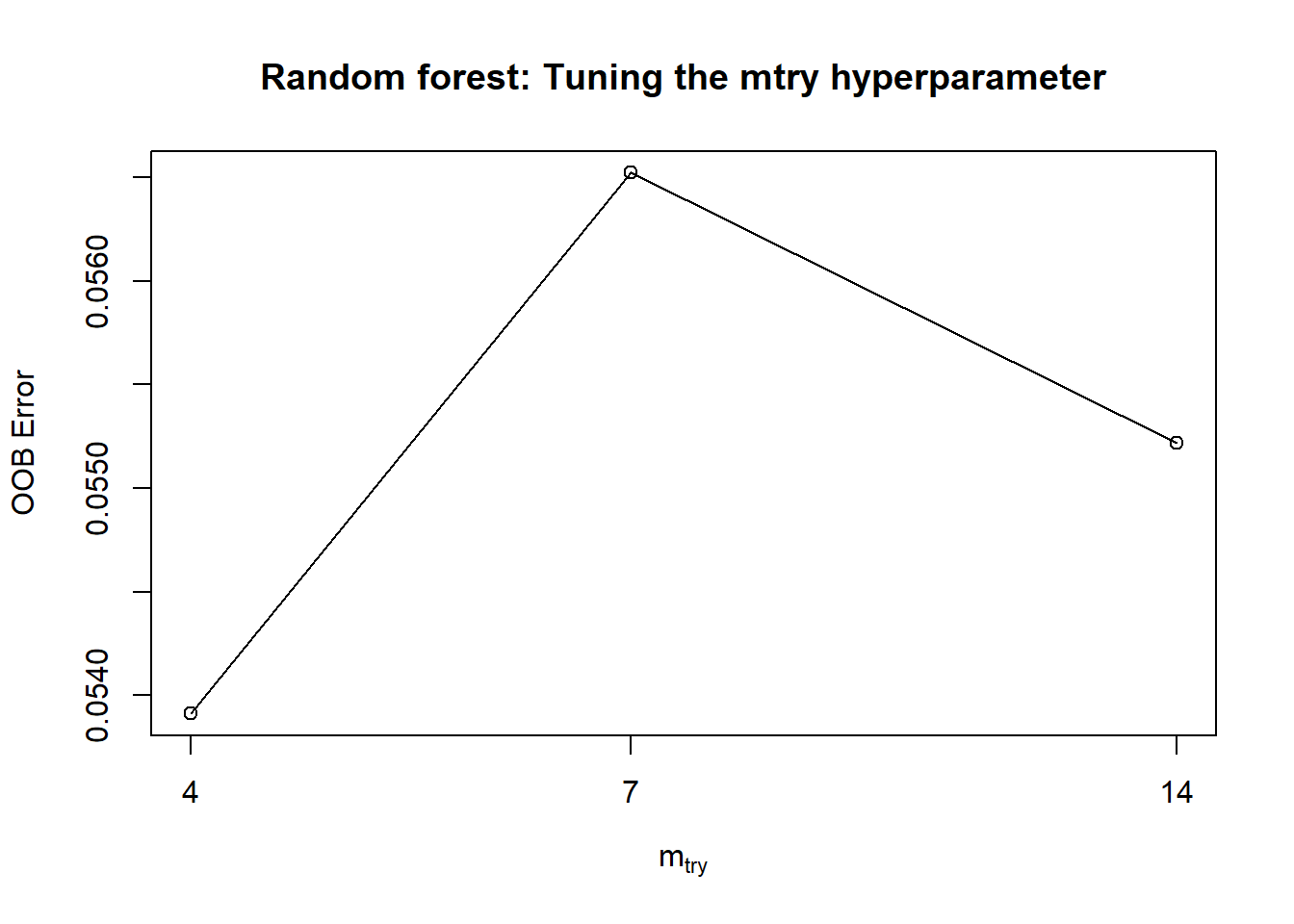

Besides tuning the ntree hyperparameter, we might also be interested in tuning the mtry hyperparameter in random forest. The random forest model may be built using the mtry value that minimises the OOB error.

tuneRF(subset(spam.train, select = -type),

spam.train$type,

ntreeTry = 100)

## mtry = 7 OOB error = 5.65%

## Searching left ...

## mtry = 4 OOB error = 5.39%

## 0.04615385 0.05

## Searching right ...

## mtry = 14 OOB error = 5.52%

## 0.02307692 0.05

## mtry OOBError

## 4.OOB 4 0.05391304

## 7.OOB 7 0.05652174

## 14.OOB 14 0.05521739

title("Random forest: Tuning the mtry hyperparameter")

# variable importance

varImpPlot(rf.mod,

main = "Random forest: Variable importance")

# multidimensional scaling plot

# green samples are non-spam,

# red samples are spam

MDSplot(rf.mod,

fac = spam.train$type,

palette = c("green","red"),

main = "Random forest: MDS")

# now, let's make some predictions

rf.pred <- predict(rf.mod,

subset(spam.test,select = -type),

type="class")

# confusion matrix

print(rf.pred.results <- table(rf.pred, spam.test$type))

##

## rf.pred nonspam spam

## nonspam 1372 80

## spam 36 813

# Accuracy of our RF model:

print(rf.accuracy <- sum(diag((rf.pred.results))) / sum(rf.pred.results))

## [1] 0.9495871Our random forest model predicts whether an email is spam or not with about 94.96% accuracy.

Visualization of performances

Let’s go ahead and make some comparisons on the performances of our model. For comparison sake, let’s also construct a logistic regression model.

log.mod <- glm(type ~ . , data = spam.train,

family = binomial(link = logit))

## Warning: glm.fit: fitted probabilities numerically 0 or 1 occurred

# predictions

log.pred.prob <- predict(log.mod,

subset(spam.test, select = -type),

type = "response")

log.pred.class <- factor(sapply(log.pred.prob,

FUN = function(x){

if(x >= 0.5) return("spam")

else return("nonspam")

}))

# confusion matrix

log.pred.results <- table(log.pred.class, spam.test$type)

# Accuracy of logistic regression model:

print(log.accuracy <- sum(diag((log.pred.results))) / sum(log.pred.results))

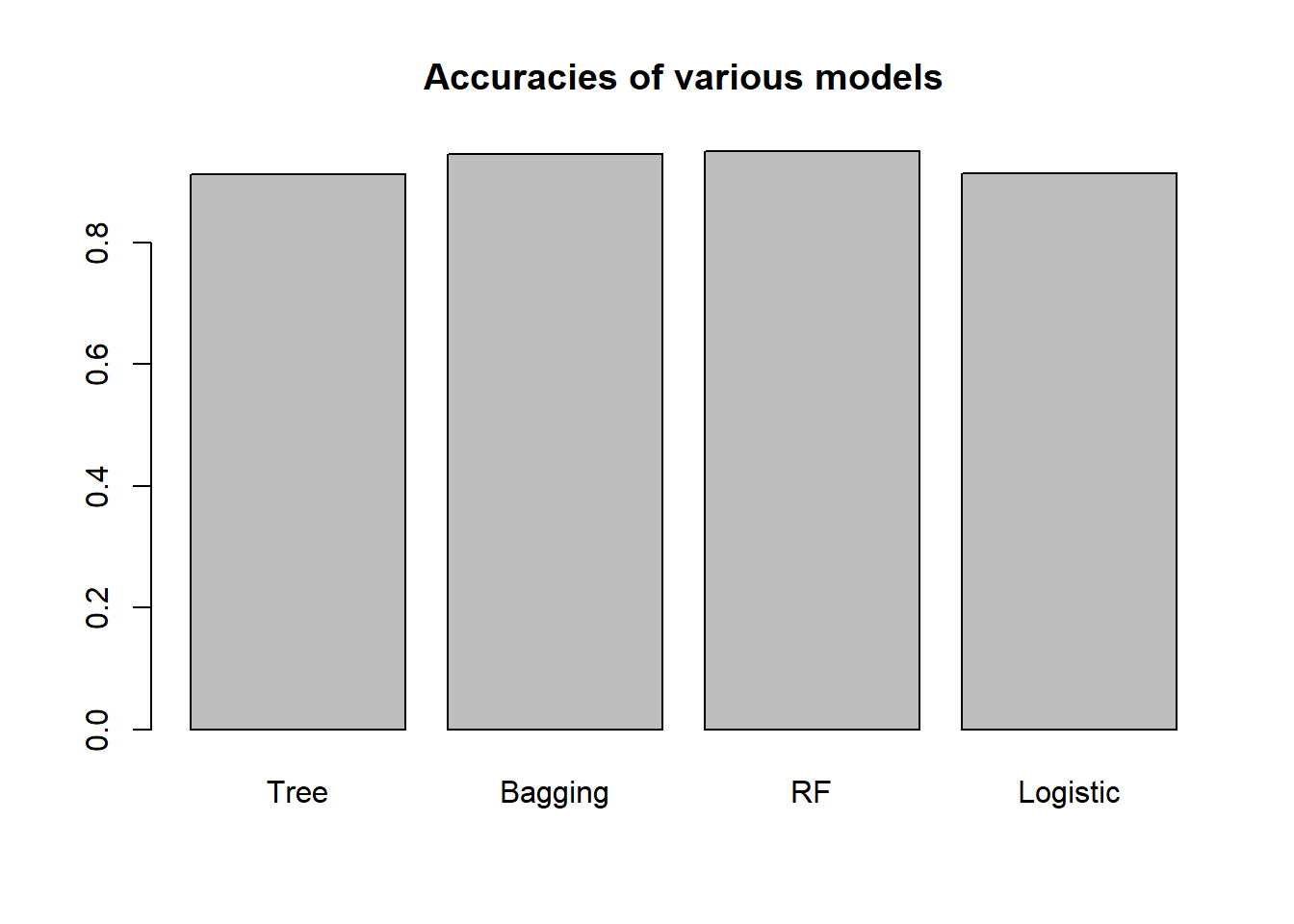

## [1] 0.9126467Now, let’s compare the performances, considering first the model accuracies.

barplot(c(tree.accuracy,

bg.accuracy,

rf.accuracy,

log.accuracy),

main="Accuracies of various models",

names.arg=c("Tree","Bagging","RF", "Logistic"))

We can see here that the ensemble models (bagging and random forest) outperforms the single decision tree, and also the logistic regression model. It turns out here that the bagging and the random forest models have about the same classification performance. Understanding the rationale of random subspace sampling (refer to slides) should allow us to appreciate the potential improvement of random forest over the bagging model.

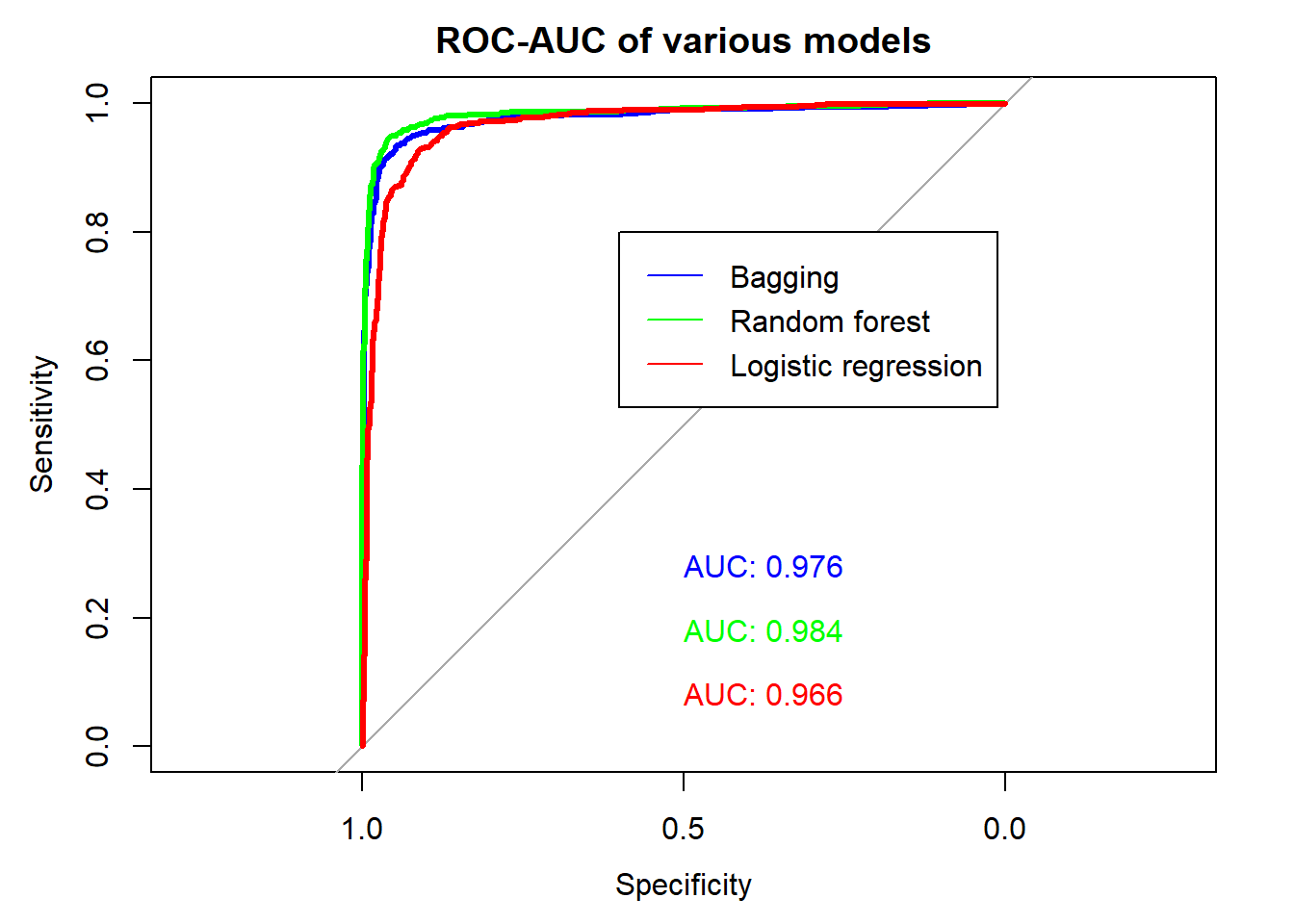

Finally, let’s plot the ROC curves of the various models. The ROC is only valid for models that give probabilistic output.

bg.pred.prob <- predict(bg.mod ,

subset(spam.test, select = -type),

type = "prob")

rf.pred.prob <- predict(rf.mod ,

subset(spam.test, select = -type),

type = "prob")

plot.roc(spam.test$type,

bg.pred.prob[,1], col = "blue",

lwd = 3, print.auc = TRUE, print.auc.y = 0.3,

main = "ROC-AUC of various models")

## Setting levels: control = nonspam, case = spam

## Setting direction: controls > cases

plot.roc(spam.test$type,

rf.pred.prob[,1], col = "green",

lwd = 3, print.auc = TRUE, print.auc.y = 0.2,

add = TRUE)

## Setting levels: control = nonspam, case = spam

## Setting direction: controls > cases

plot.roc(spam.test$type,

log.pred.prob, col = "red",

lwd = 3, print.auc = TRUE, print.auc.y = 0.1,

add = TRUE)

## Setting levels: control = nonspam, case = spam

## Setting direction: controls < cases

legend(x = 0.6, y = 0.8, legend = c("Bagging",

"Random forest",

"Logistic regression"),

col = c("blue", "green", "red"), lwd = 1)

Tree-based methods for regression

In the following section, we will consider the use of tree-based methods for regression. The materials that follows are analogous to that above, if not the similar.

Preparation

library(tree)

library(randomForest)

data(imports85)

imp <- imports85

# The following data preprocessing steps on

# the imports85 dataset are suggested by

# the authors of the randomForest package

# look at

# > ?imports85

imp <- imp[,-2] # Too many NAs in normalizedLosses.

imp <- imp[complete.cases(imp), ]

# ## Drop empty levels for factors

imp[] <- lapply(imp, function(x) if (is.factor(x)) x[, drop=TRUE] else x)

# Also removing the numOfCylinders and fuelSystem

# variables due to sparsity of data

# to see this, run the following lines:

# > table(imp$numOfCylinders)

# > table(imp$fuelSystem)

# This additional step is only necessary because we will be

# making comparisons between the tree-based models

# and linear regression, and linear regression cannot

# handle sparse data well

imp <- subset(imp, select = -c(numOfCylinders,fuelSystem))

# also removing the make variable

imp <- subset(imp, select = -make)

# Preparation for cross validation:

# split the dataset into 2 halves,

# 96 samples for training and 97 for testing

num.samples <- nrow(imp) # 193

num.train <- round(num.samples / 2) # 96

num.test <- num.samples - num.train # 97

num.var <- ncol(imp) # 25

# set up the indices

set.seed(150715)

idx <- sample(1:num.samples)

train.idx <- idx[seq(num.train)]

test.idx <- setdiff(idx,train.idx)

# subset the data

imp.train <- imp[train.idx,]

imp.test <- imp[test.idx,]

str(imp.train)

## 'data.frame': 96 obs. of 22 variables:

## $ symboling : int 3 1 1 1 3 1 1 1 0 2 ...

## $ fuelType : Factor w/ 2 levels "diesel","gas": 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 1 2 2 ...

## $ aspiration : Factor w/ 2 levels "std","turbo": 1 1 1 1 2 1 1 1 1 1 ...

## $ numOfDoors : Factor w/ 2 levels "four","two": 2 1 2 2 2 1 2 2 1 2 ...

## $ bodyStyle : Factor w/ 5 levels "convertible",..: 1 4 4 3 3 3 3 4 4 4 ...

## $ driveWheels : Factor w/ 3 levels "4wd","fwd","rwd": 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 3 2 ...

## $ engineLocation : Factor w/ 2 levels "front","rear": 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 ...

## $ wheelBase : num 94.5 93.1 94.5 93.7 95.9 93.7 93.1 94.5 113 99.8 ...

## $ length : num 159 167 165 157 173 ...

## $ width : num 64.2 64.2 63.8 63.8 66.3 63.8 64.2 63.8 69.6 66.3 ...

## $ height : num 55.6 54.1 54.5 50.8 50.2 50.6 54.1 54.5 52.8 53.1 ...

## $ curbWeight : int 2254 1945 1918 1876 2921 1967 1905 2017 4066 2507 ...

## $ engineType : Factor w/ 5 levels "dohc","l","ohc",..: 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 1 3 ...

## $ engineSize : int 109 91 97 90 156 90 91 103 258 136 ...

## $ bore : num 3.19 3.03 3.15 2.97 3.59 2.97 3.03 2.99 3.63 3.19 ...

## $ stroke : num 3.4 3.15 3.29 3.23 3.86 3.23 3.15 3.47 4.17 3.4 ...

## $ compressionRatio: num 8.5 9 9.4 9.41 7 9.4 9 21.9 8.1 8.5 ...

## $ horsepower : int 90 68 69 68 145 68 68 55 176 110 ...

## $ peakRpm : int 5500 5000 5200 5500 5000 5500 5000 4800 4750 5500 ...

## $ cityMpg : int 24 31 31 37 19 31 31 45 15 19 ...

## $ highwayMpg : int 29 38 37 41 24 38 38 50 19 25 ...

## $ price : int 11595 6695 6649 5572 14869 6229 6795 7099 35550 15250 ...

str(imp.test)

## 'data.frame': 97 obs. of 22 variables:

## $ symboling : int -1 0 1 0 3 0 0 3 2 2 ...

## $ fuelType : Factor w/ 2 levels "diesel","gas": 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 ...

## $ aspiration : Factor w/ 2 levels "std","turbo": 1 1 2 1 2 1 1 1 1 1 ...

## $ numOfDoors : Factor w/ 2 levels "four","two": 1 1 2 1 2 2 1 2 2 1 ...

## $ bodyStyle : Factor w/ 5 levels "convertible",..: 4 3 3 4 3 3 4 3 3 4 ...

## $ driveWheels : Factor w/ 3 levels "4wd","fwd","rwd": 2 2 3 1 2 2 2 2 1 2 ...

## $ engineLocation : Factor w/ 2 levels "front","rear": 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 ...

## $ wheelBase : num 102.4 97.2 102.7 97 95.9 ...

## $ length : num 176 173 178 172 173 ...

## $ width : num 66.5 65.2 68 65.4 66.3 65.2 65.2 66.5 63.8 66.5 ...

## $ height : num 54.9 54.7 54.8 54.3 50.2 53.3 54.1 56.1 55.7 56.1 ...

## $ curbWeight : int 2414 2324 2910 2385 2811 2236 2304 2658 2240 2758 ...

## $ engineType : Factor w/ 5 levels "dohc","l","ohc",..: 3 3 3 4 3 3 3 3 4 3 ...

## $ engineSize : int 122 120 140 108 156 110 110 121 108 121 ...

## $ bore : num 3.31 3.33 3.78 3.62 3.6 3.15 3.15 3.54 3.62 3.54 ...

## $ stroke : num 3.54 3.47 3.12 2.64 3.9 3.58 3.58 3.07 2.64 3.07 ...

## $ compressionRatio: num 8.7 8.5 8 9 7 9 9 9.31 8.7 9.3 ...

## $ horsepower : int 92 97 175 82 145 86 86 110 73 110 ...

## $ peakRpm : int 4200 5200 5000 4800 5000 5800 5800 5250 4400 5250 ...

## $ cityMpg : int 27 27 19 24 19 27 27 21 26 21 ...

## $ highwayMpg : int 32 34 24 25 24 33 33 28 31 28 ...

## $ price : int 10898 8949 16503 9233 12964 7895 8845 11850 7603 15510 ...

# take a quick look

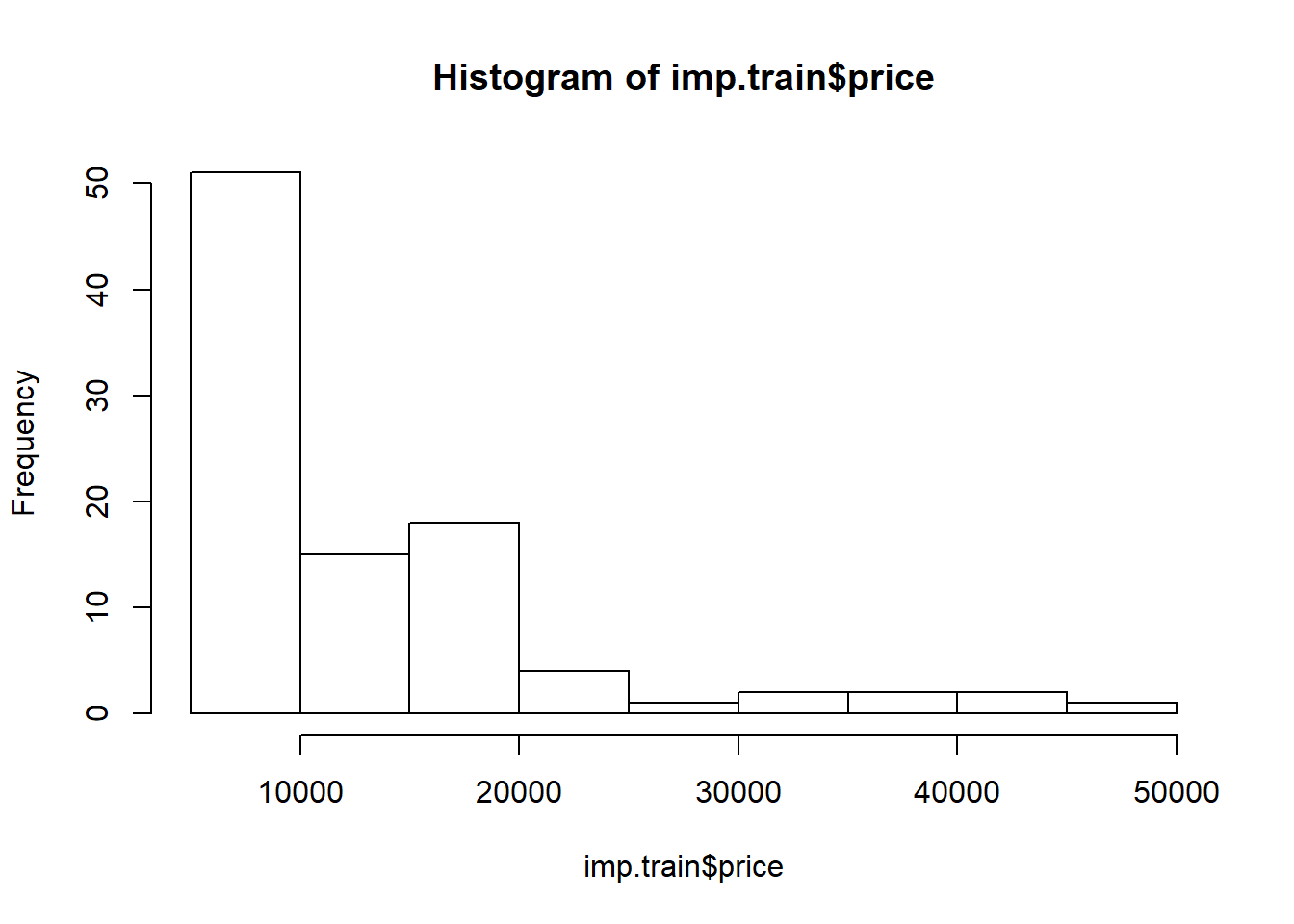

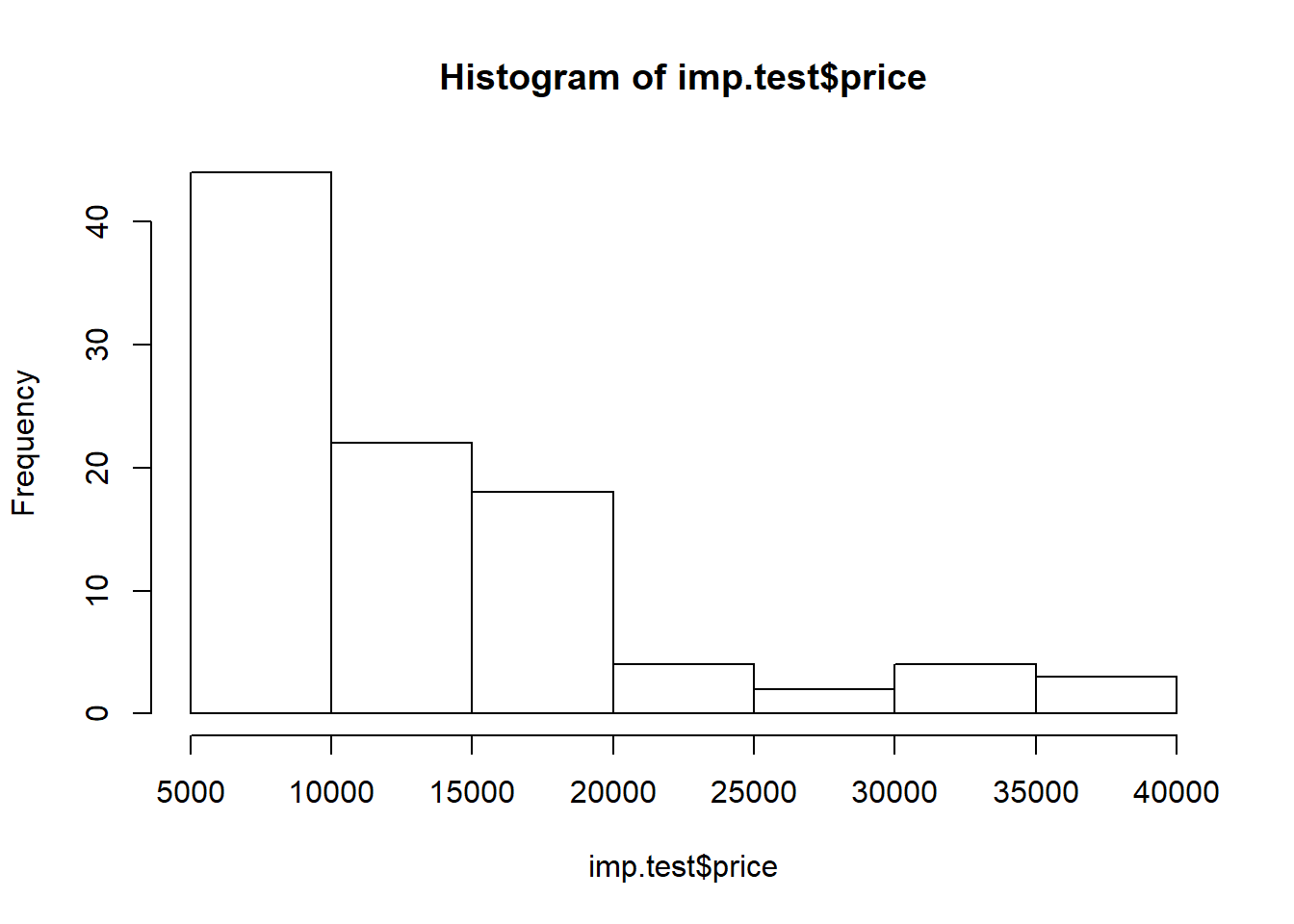

hist(imp.train$price)

hist(imp.test$price)

We will be predicting the price of imported automobiles in this example. While tree-based methods are scale-invariant with respect to predictor variables, this is not true for the response variable. Hence, let’s take a log-transformation on price here.

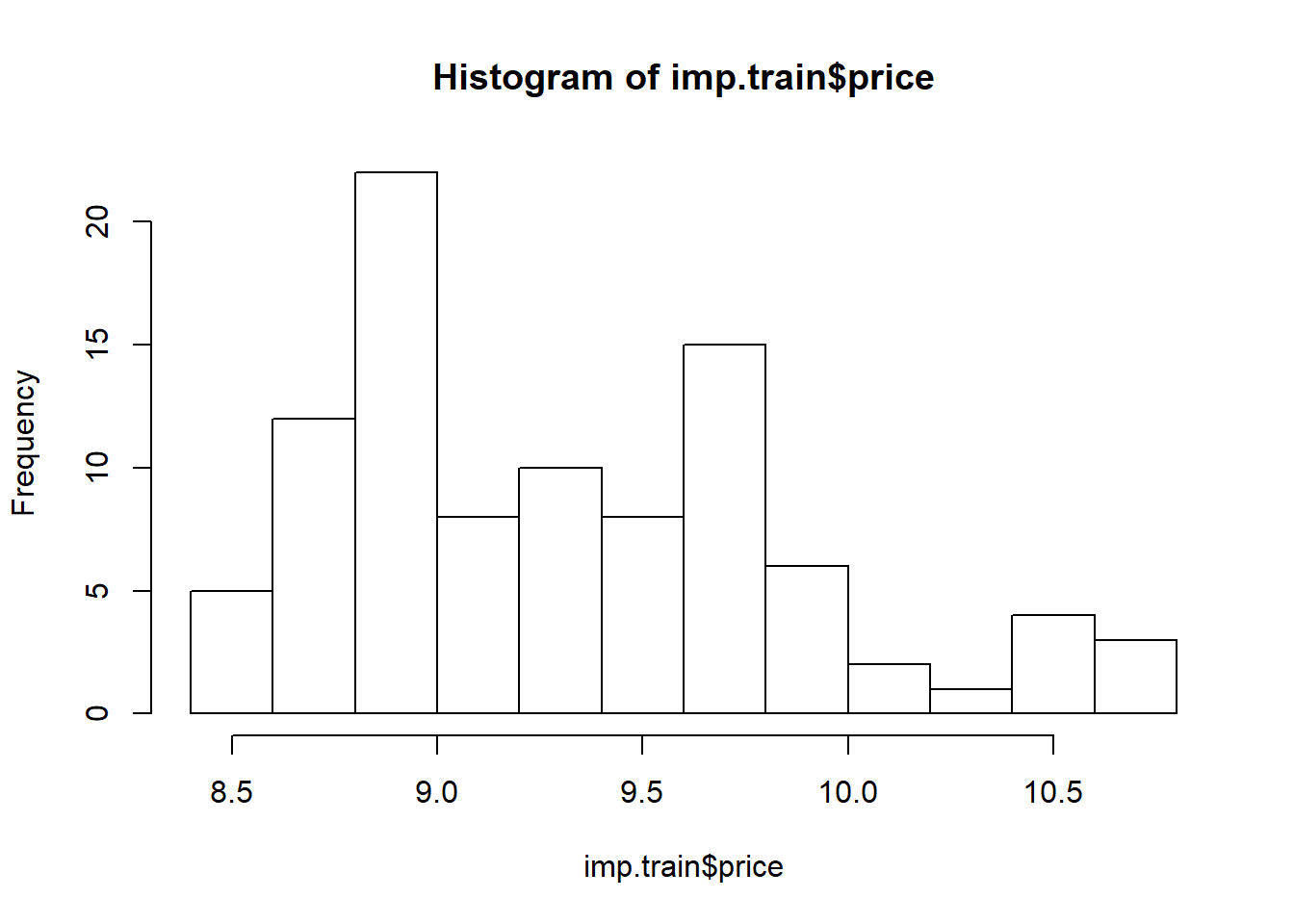

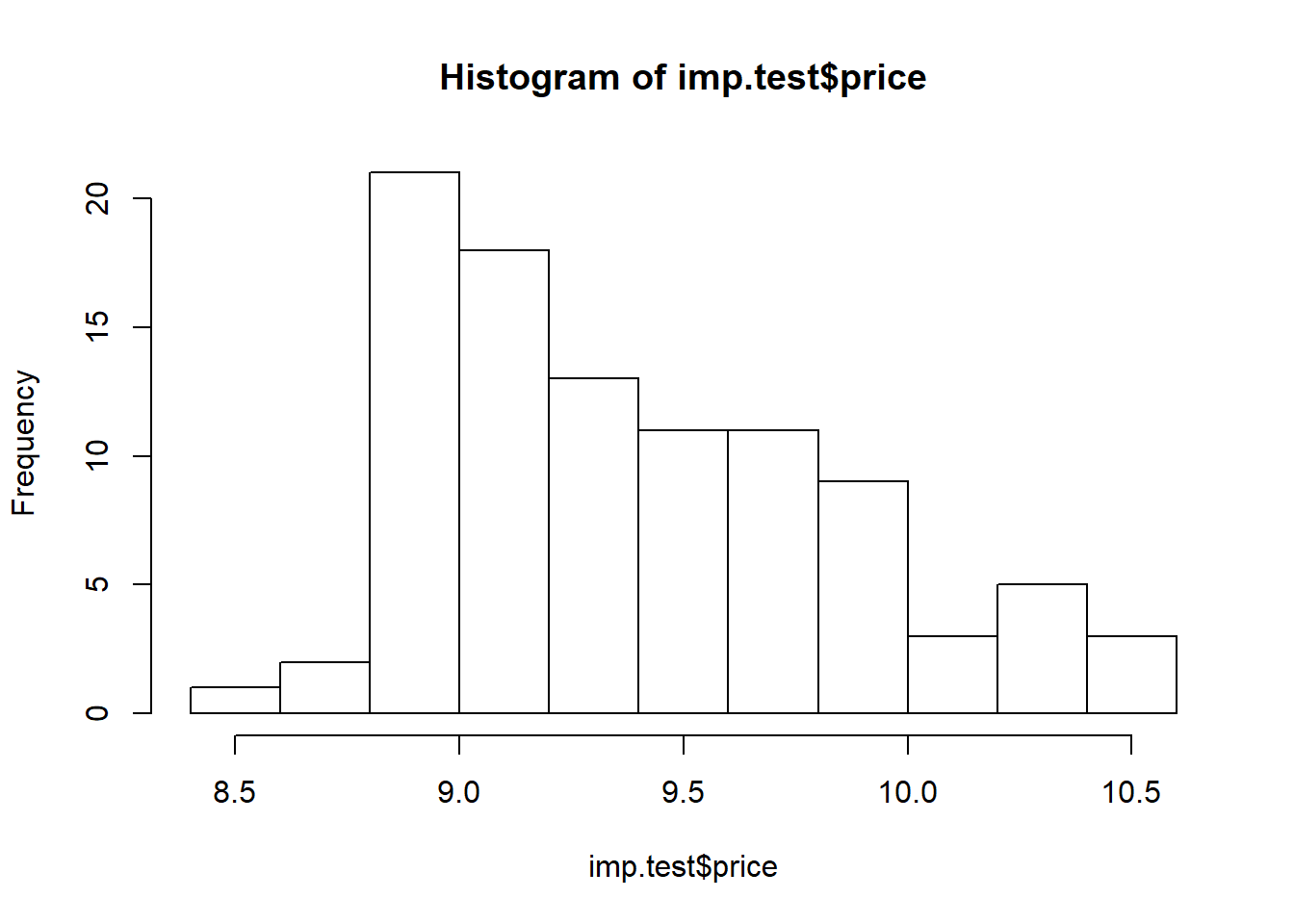

imp.train$price <- log(imp.train$price)

imp.test$price <- log(imp.test$price)

# take a look again

hist(imp.train$price)

hist(imp.test$price)

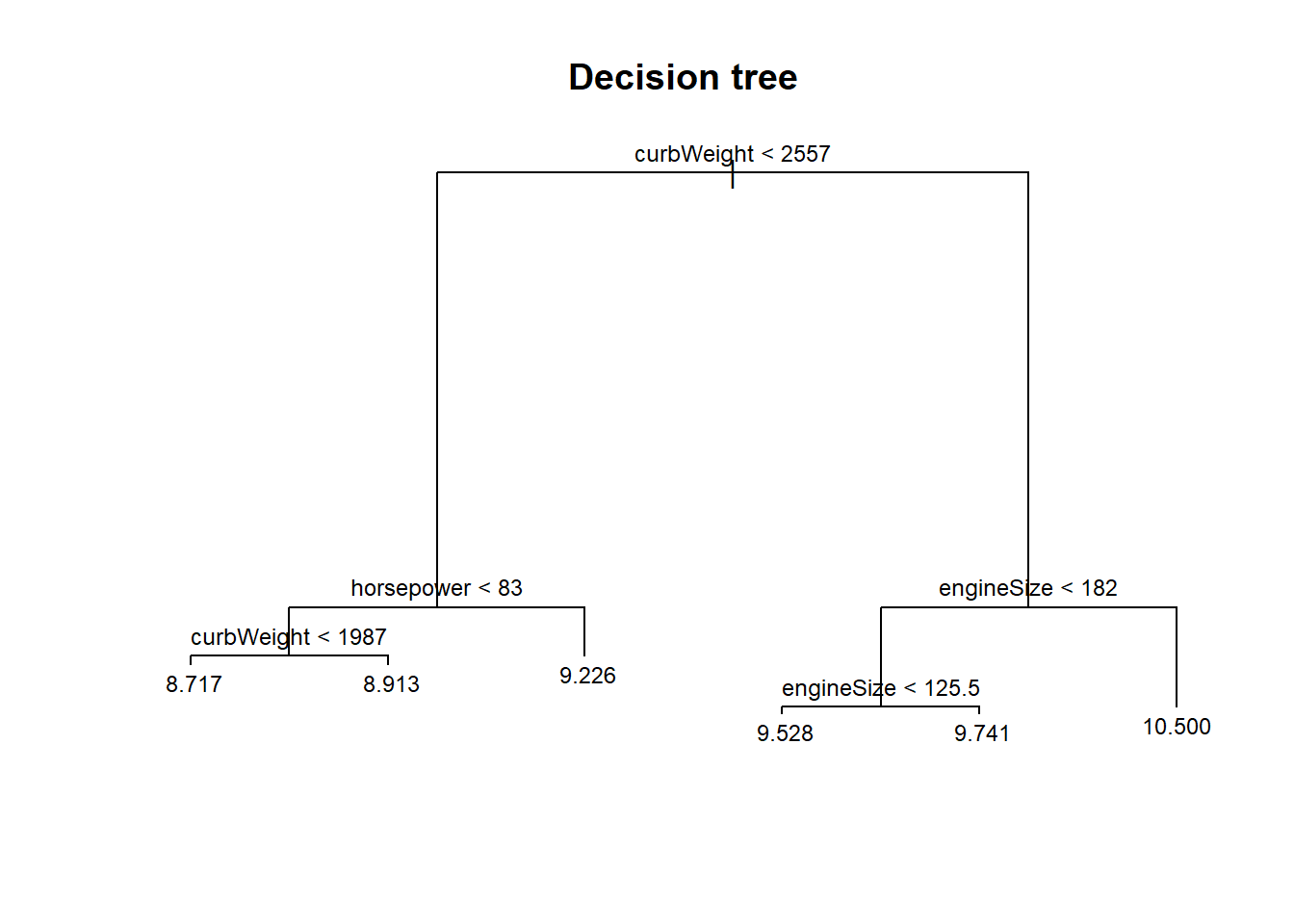

Decision tree

Done with the preparation, let’s begin with decision trees.

# Construct decision tree model

tree.mod <- tree(price ~ ., data = imp.train)

# here's how the model looks like

plot(tree.mod)

title("Decision tree")

text(tree.mod, cex = 0.75)

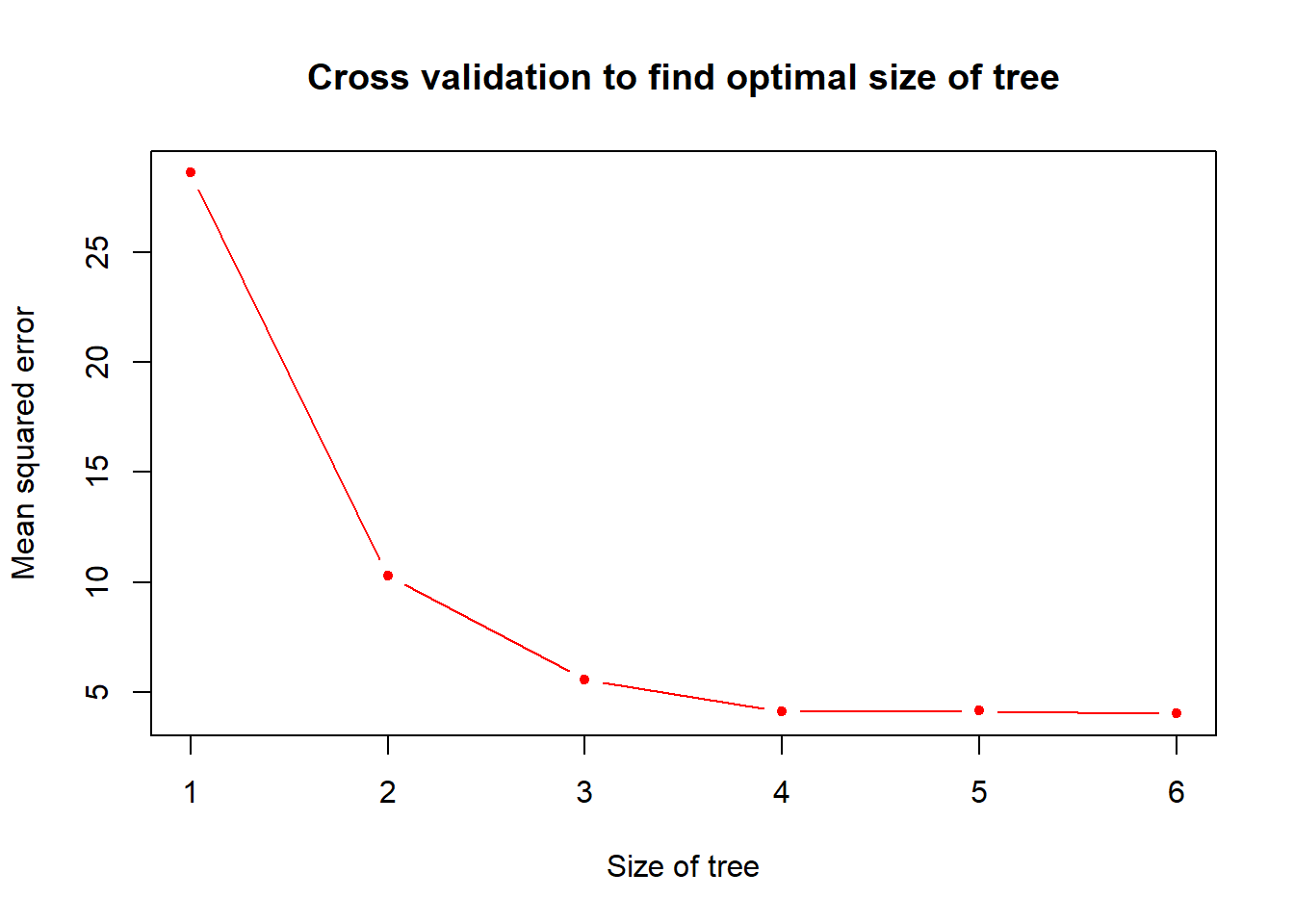

# let's see if our decision tree requires pruning

cv.prune <- cv.tree(tree.mod, FUN = prune.tree)

plot(cv.prune$size, cv.prune$dev, pch = 20, col = "red", type = "b",

main = "Cross validation to find optimal size of tree",

xlab = "Size of tree", ylab = "Mean squared error")

# looks fine

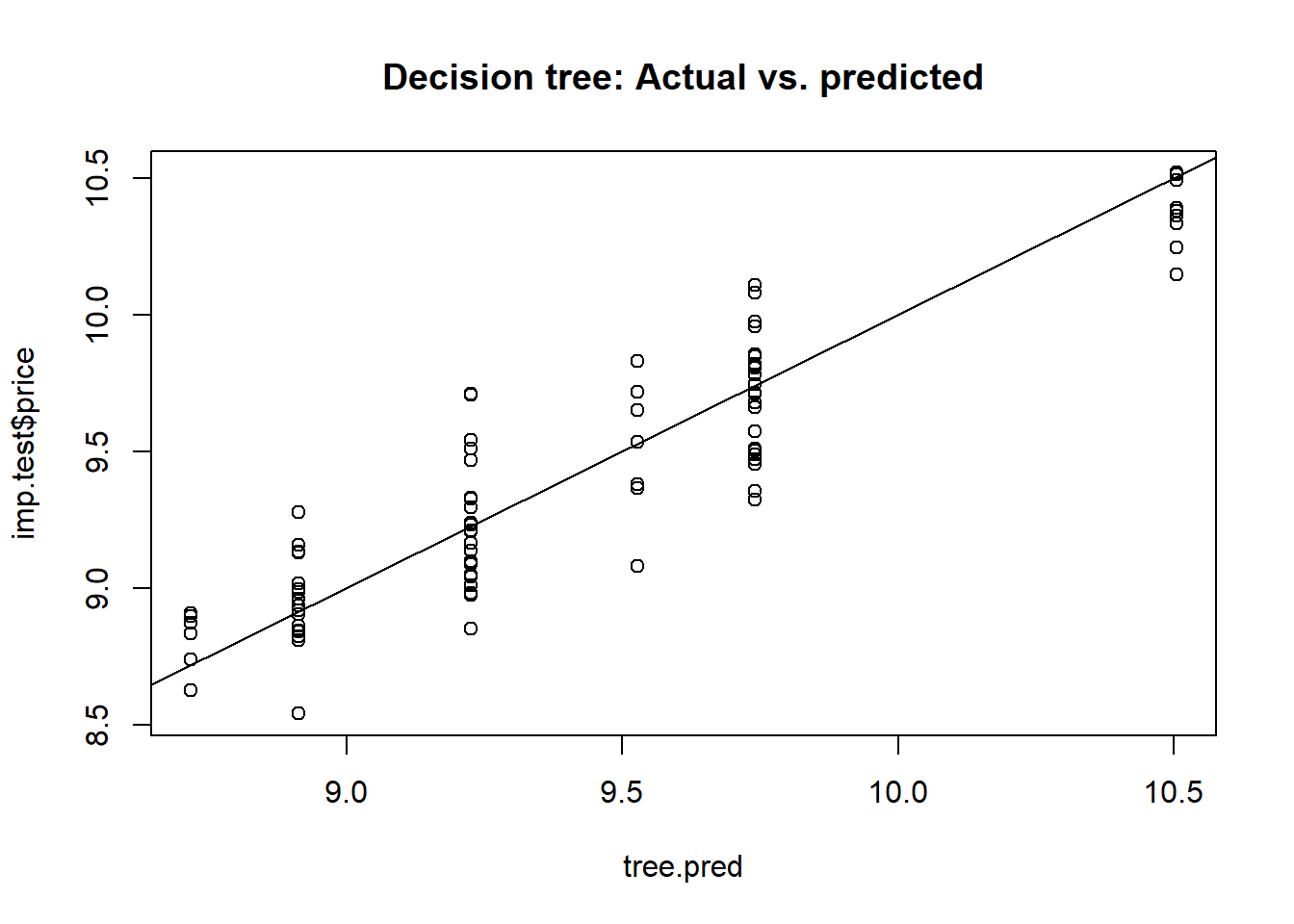

# now let's make some predictions

tree.pred <- predict(tree.mod,

subset(imp.test,select = -price),

type = "vector")

# Comparing our predictions with the test data:

plot(tree.pred, imp.test$price, main = "Decision tree: Actual vs. predicted")

abline(a = 0, b = 1) # A prediction with zero error will lie on the y = x line

# What is the MSE of our model?

print(tree.mse <- mean((tree.pred - imp.test$price) ** 2))

## [1] 0.0391897Our decision tree model predicts the price of imported automobiles with a mean squared error of 0.0392. As with the previous section, we will make comparsions on model performances later.

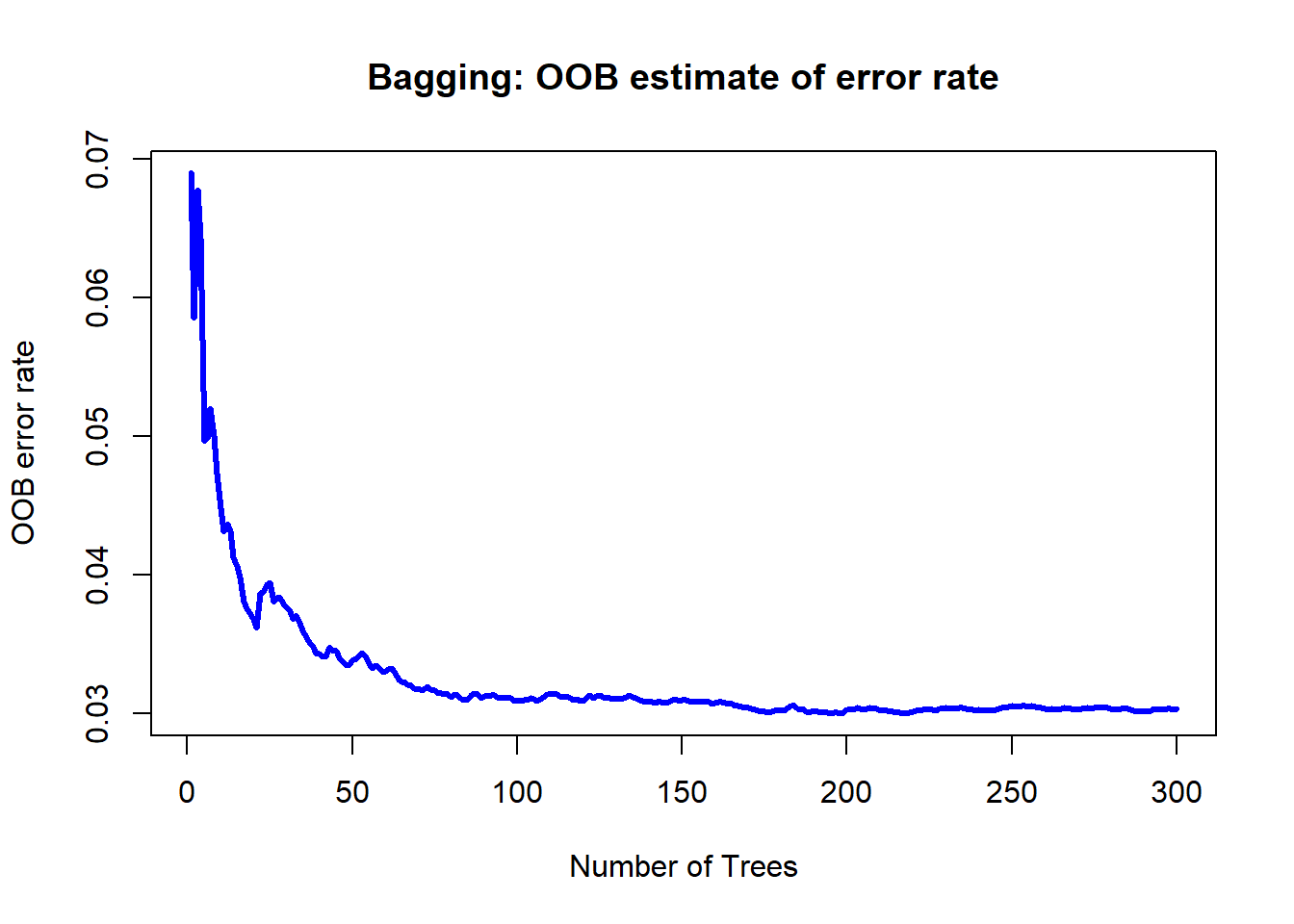

Bagging

Next, bagging.

bg.mod<-randomForest(price ~ ., data = imp.train,

mtry = num.var - 1, # try all variables at each split, except the response variable

ntree = 300,

importance = TRUE)

# Out-of-bag (OOB) error rate as a function of num. of trees

# here, the error is the mean squared error,

# not classification error

plot(bg.mod$mse, type = "l", lwd = 3, col = "blue",

main = "Bagging: OOB estimate of error rate",

xlab = "Number of Trees", ylab = "OOB error rate")

# variable importance

varImpPlot(bg.mod,

main = "Bagging: Variable importance")

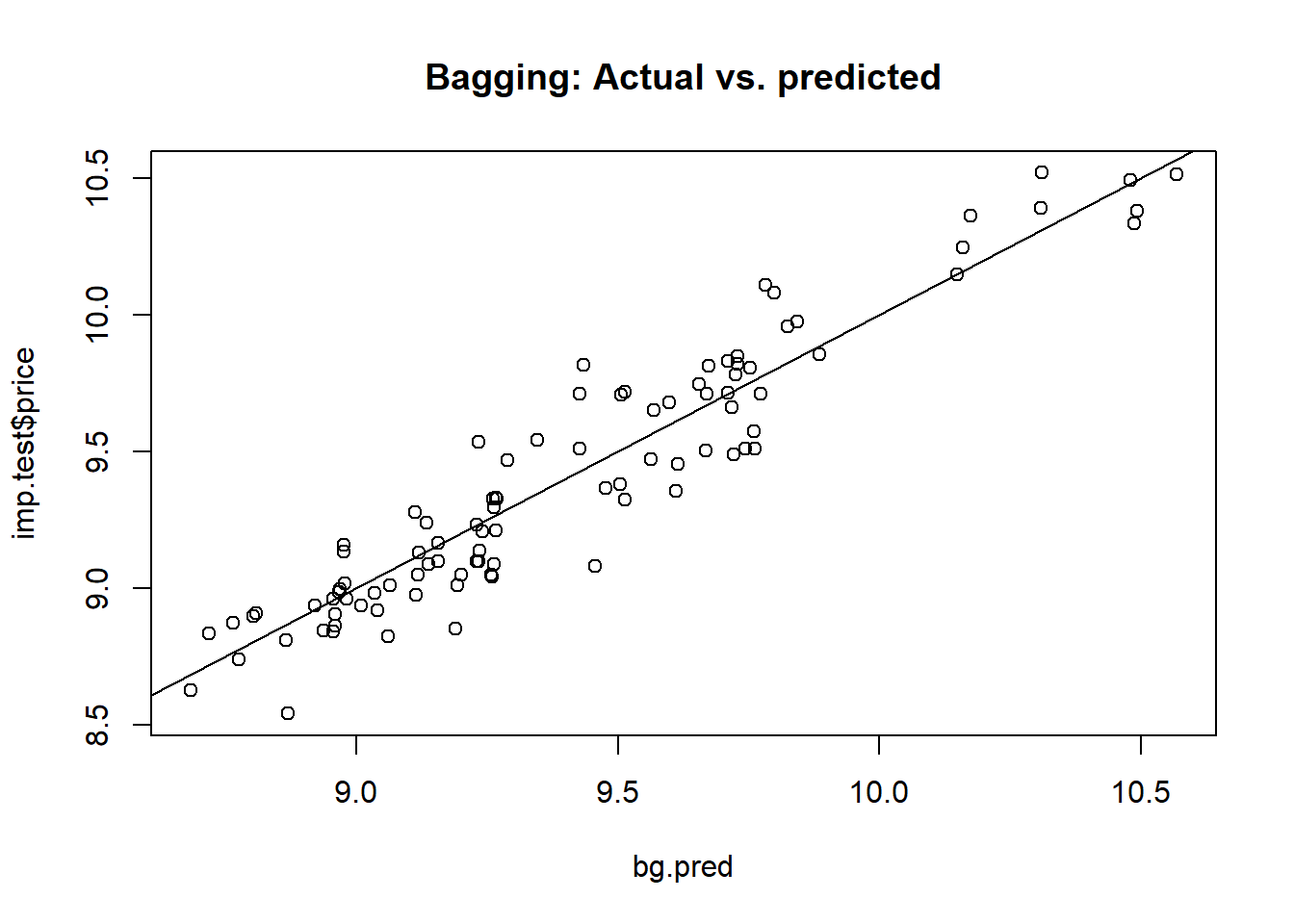

# let's make some predictions

bg.pred <- predict(bg.mod,

subset(imp.test,select = -price))

# Comparing our predictions with test data:

plot(bg.pred,imp.test$price, main = "Bagging: Actual vs. predicted")

abline(a = 0, b = 1)

# MSE of bagged model

print(bg.mse <- mean((bg.pred - imp.test$price) ** 2))

## [1] 0.02298332Our bagging model predicts the price of imported automobiles with a mean squared error of 0.023.

Random forest

Finally, the random forest model.

rf.mod<-randomForest(price ~ ., data = imp.train,

mtry = floor((num.var - 1) / 3), # 7; only difference from bagging is here

ntree = 300,

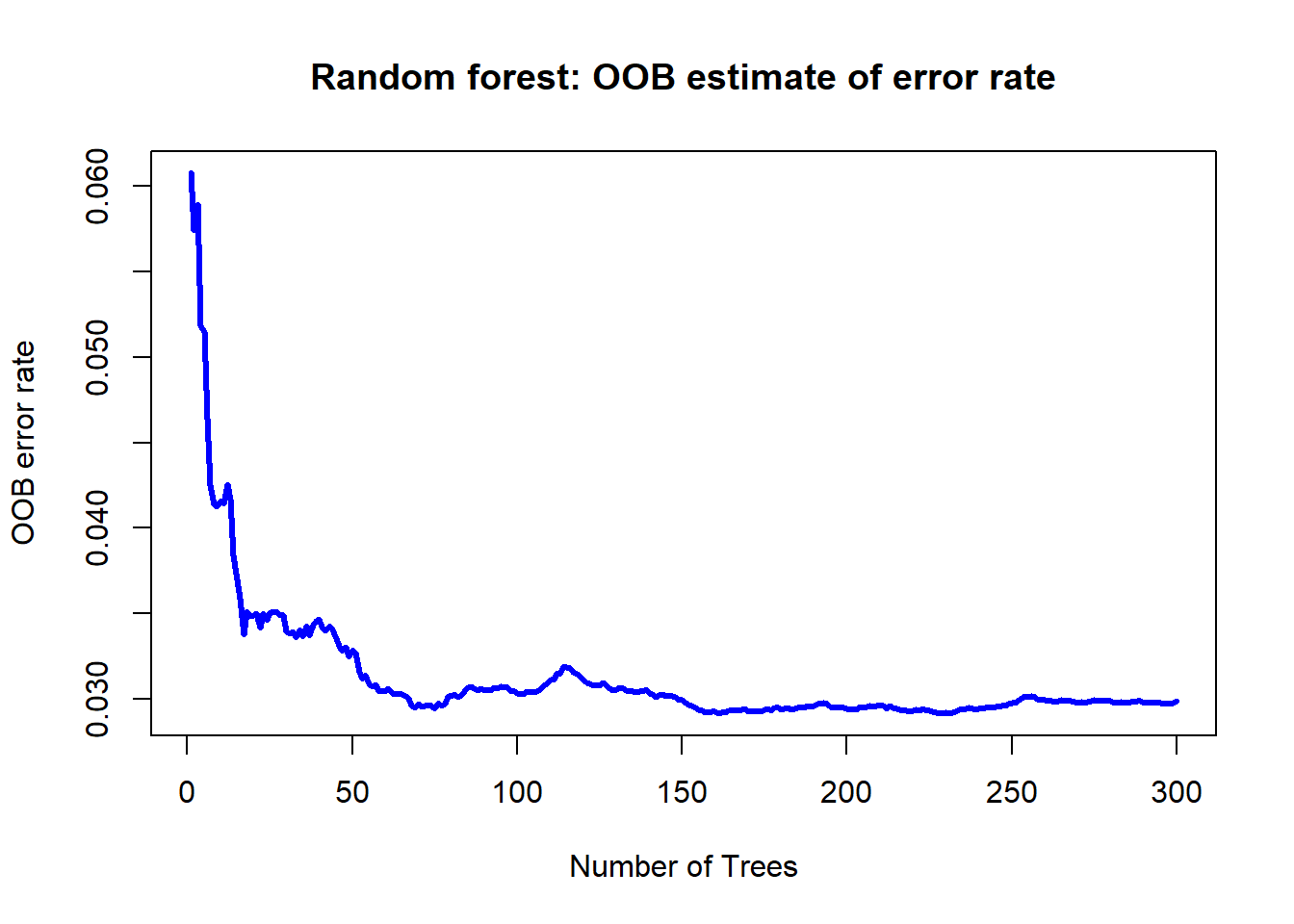

importance = TRUE)

# Out-of-bag (OOB) error rate as a function of num. of trees

plot(rf.mod$mse, type = "l", lwd = 3, col = "blue",

main = "Random forest: OOB estimate of error rate",

xlab = "Number of Trees", ylab = "OOB error rate")

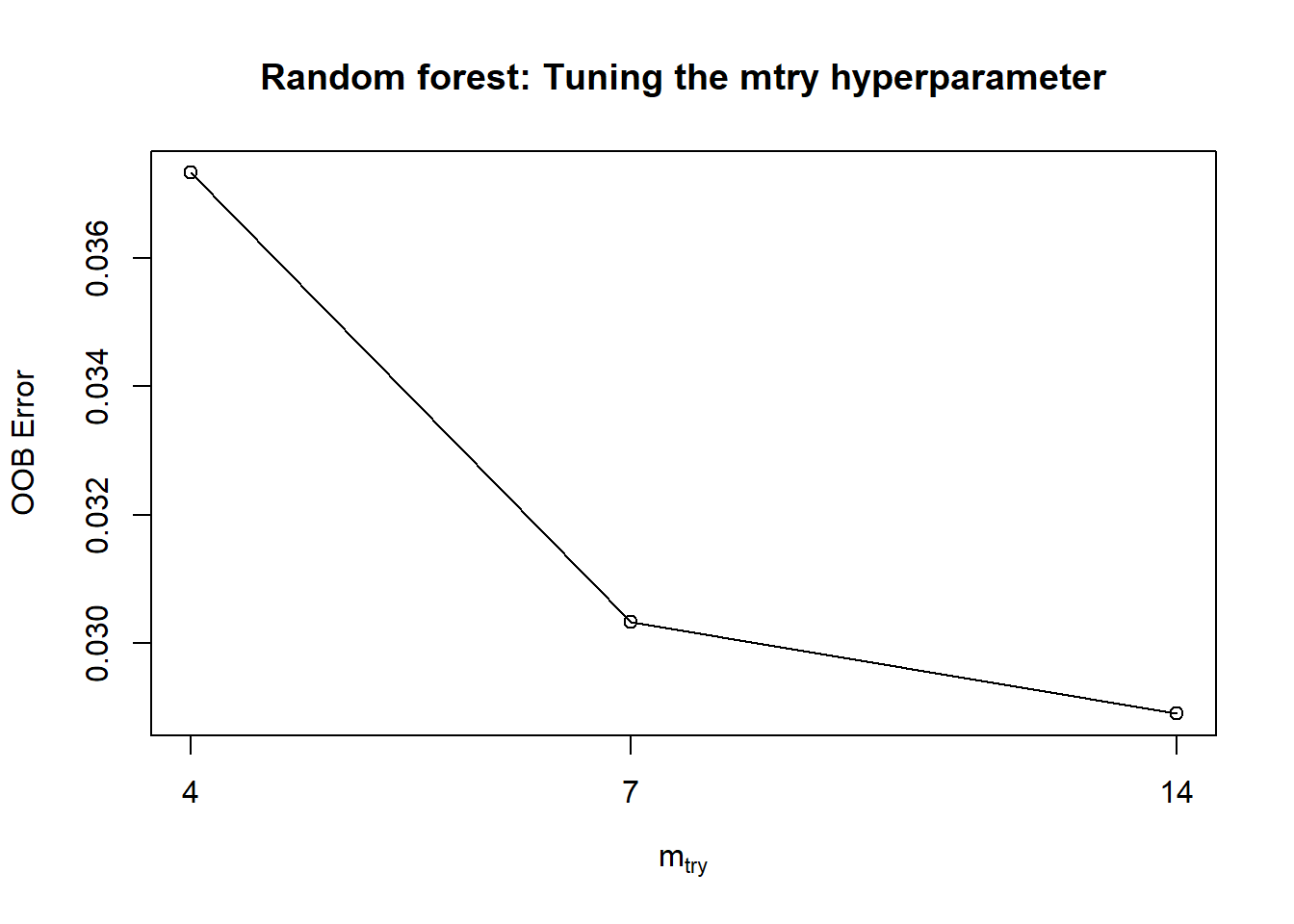

# tuning the mtry hyperparameter:

# model may be rebuilt if desired

tuneRF(subset(imp.train, select = -price),

imp.train$price,

ntreetry = 100)

## mtry = 7 OOB error = 0.03033217

## Searching left ...

## mtry = 4 OOB error = 0.03732523

## -0.2305491 0.05

## Searching right ...

## mtry = 14 OOB error = 0.0289063

## 0.04700843 0.05

## mtry OOBError

## 4 4 0.03732523

## 7 7 0.03033217

## 14 14 0.02890630

title("Random forest: Tuning the mtry hyperparameter")

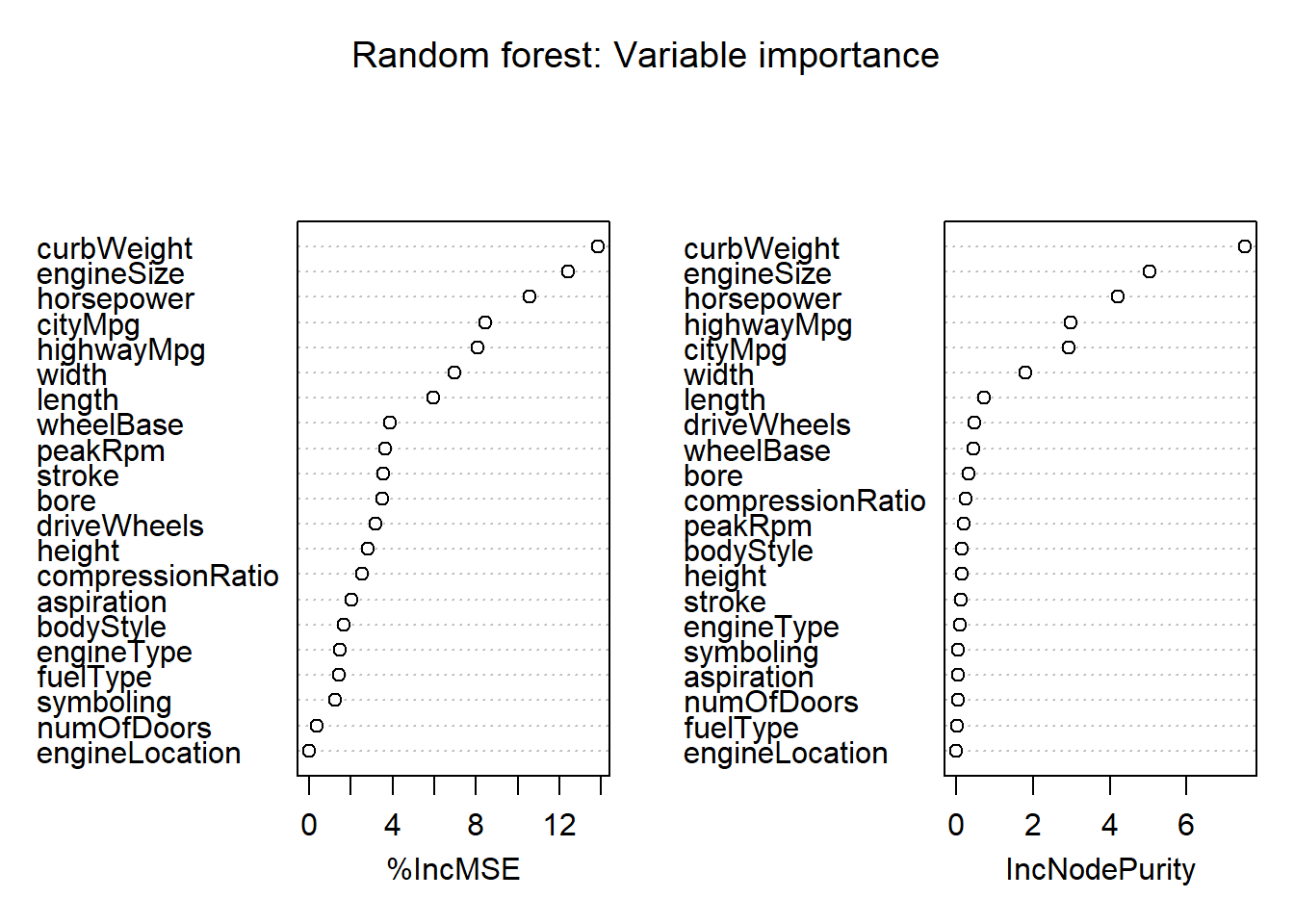

# variable importance

varImpPlot(rf.mod,

main = "Random forest: Variable importance")

# let's make some predictions

rf.pred <- predict(rf.mod,

subset(imp.test, select = -price))

# Comparing our predictions with test data:

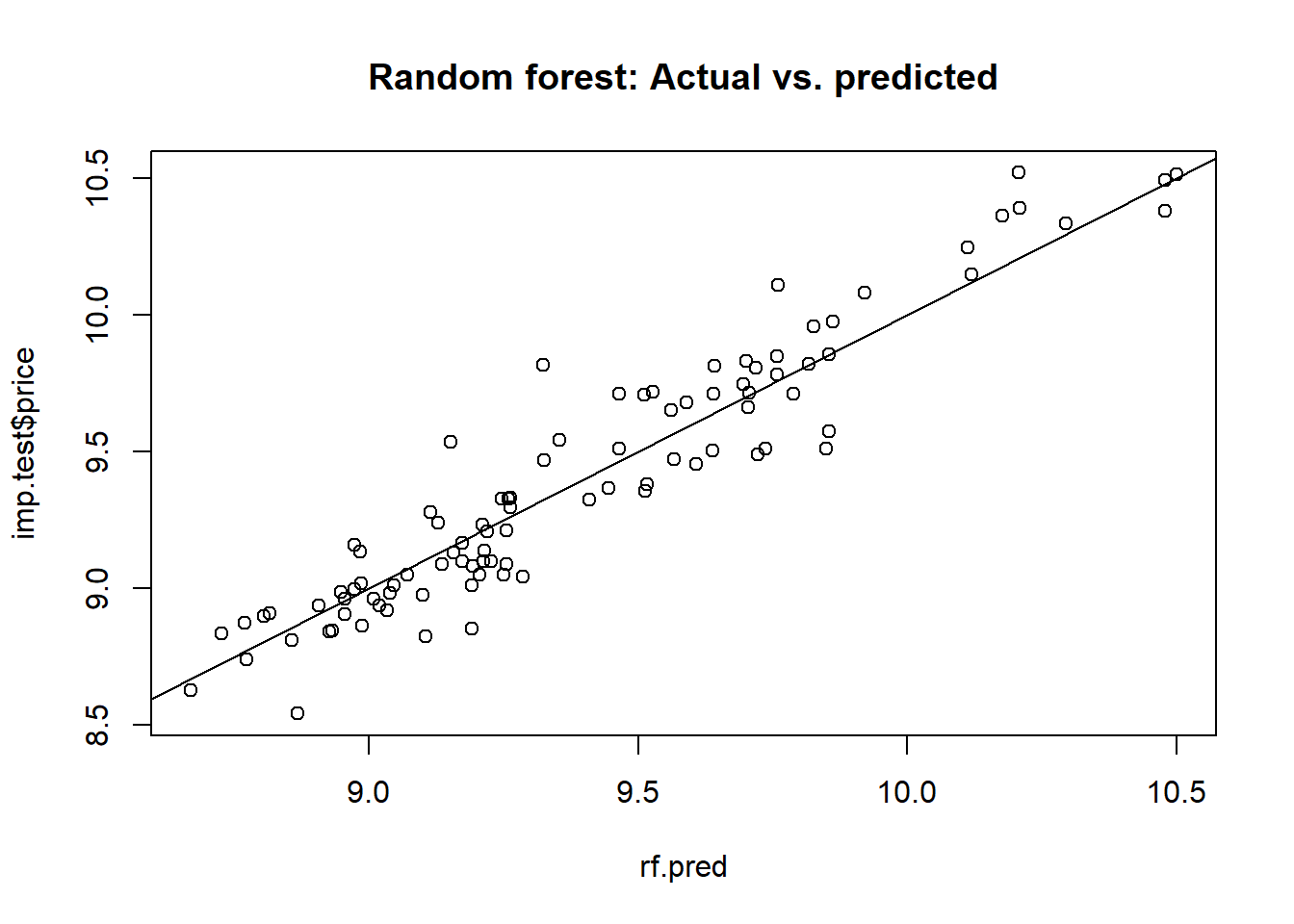

plot(rf.pred, imp.test$price, main = "Random forest: Actual vs. predicted")

abline(a = 0, b = 1)

# MSE of RF model

print(rf.mse <- mean((rf.pred - imp.test$price) ** 2))

## [1] 0.02317156Our random forest model incurs a mean squared error of 0.0232 for the prediction of imported automobile prices

Visualization of performances

For comparison purposes, let’s also construct a ordinary least squares (linear regression) model.

ols.mod <- lm(price ~ ., data = imp.train)

# predictions

ols.pred <- predict(ols.mod,

subset(imp.test, select = -price))

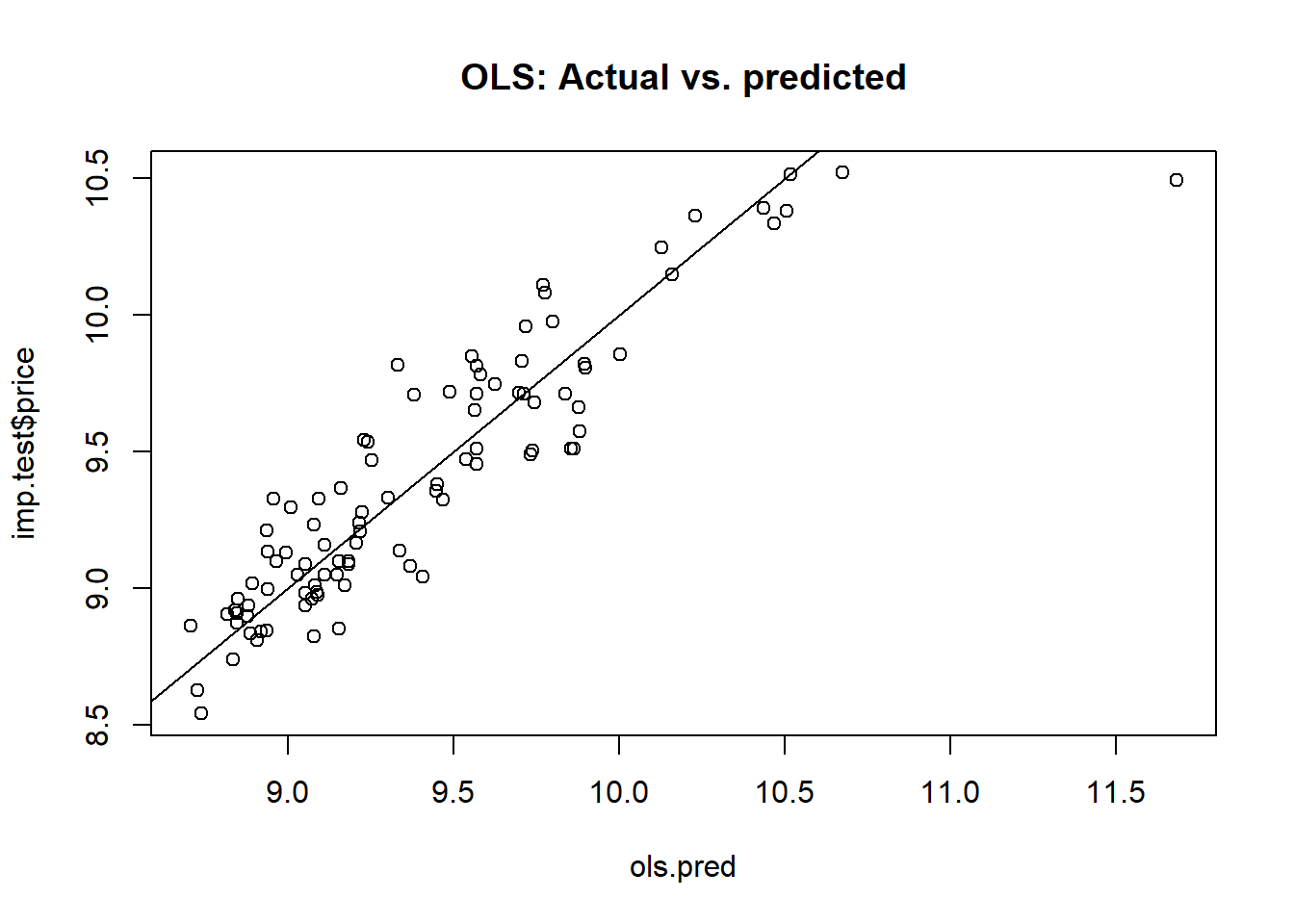

# comparisons with test data:

plot(ols.pred, imp.test$price, main = "OLS: Actual vs. predicted")

abline(a = 0, b = 1)

# MSE

print(ols.mse <- mean((ols.pred-imp.test$price) ** 2))

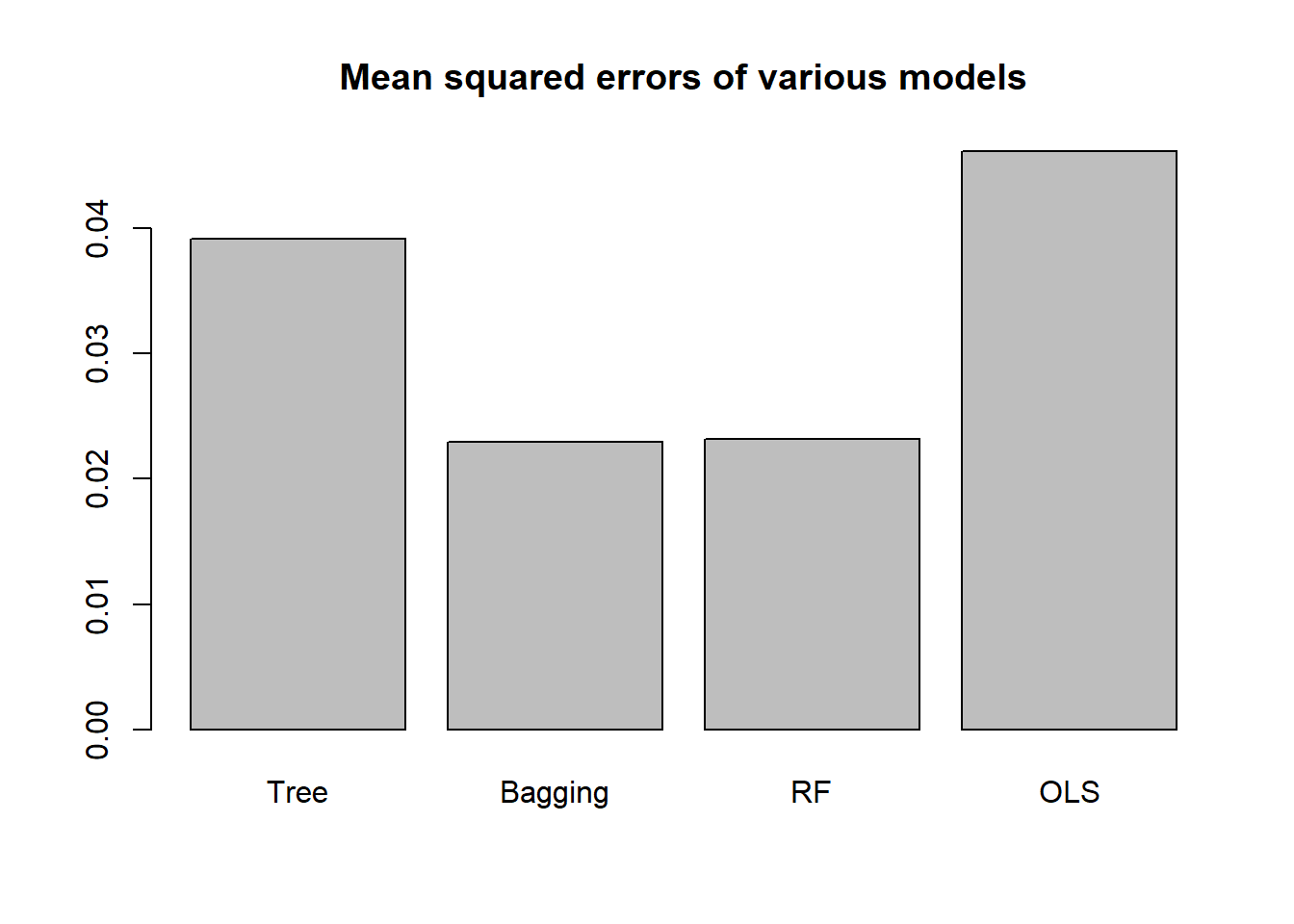

## [1] 0.04616828Now, let’s compare their performances.

# Comparing MSEs of various models:

barplot(c(tree.mse,

bg.mse,

rf.mse,

ols.mse),

main = "Mean squared errors of various models",

names.arg = c("Tree", "Bagging", "RF", "OLS"))

Our top performer here is the random forest model, followed by the bagging model.